The sharp trajectory of artist Genieve Figgis

From the market’s discovery of her work, to her influences and the artists she’s shown alongside, the popularity of Figgis’s playfully grotesque works can tell us a few things about the art world today.

When the American artist Richard Prince bought a work by then lesser-known Irish painter Genieve Figgis in 2014, later publishing the first book of her work (Making Love with the Devil) under his clandestine moniker Fulton Ryder, it launched Figgis into the public eye. The oil on wood painting, Lady in a landscape with a Bird (2013), that he purchased for his collection epitomises the eerie, misshapen figures that populate her work. In the accompanying text for the publication, the writer David Rimanelli described Figgis’s characters as emanating from “some luminescent netherworld … enchanted and menacing by turns”.

© Genieve Figgis.

Prince had discovered Figgis’s practice through Twitter, which she had been using to share her new paintings, along with posting on Instagram. She was working from a makeshift studio in her garden, having graduated from art school in her 30s, after initially prioritising holding a stable job in order to raise her family. Figgis had shown at small gallery spaces in Dublin and London, but it was the 2014 exhibition ‘Good Morning, Midnight’ at New York’s Half Gallery that was crucial for the rise in her international reputation. The art critic Roberta Smith wrote favourably about the show in The New York Times, comparing her work to “Goya, Karen Kilimnik and George Condo”.

Figgis, who is 49, now has nearly 30 solo and group exhibitions to her name. In 2015, she signed with the eponymous blue-chip commercial gallerist Almine Rech, who has spaces in Brussels, Paris, New York, Shanghai and London. Figgis has had five solo shows at various Almine Rech galleries, and in 2019, her work was exhibited in New York alongside other in-demand contemporary painters on the gallery roster (including Marcus Jahmal, Sam McKinniss, Claire Tabouret, and Chloe Wise) as part of ‘Line Up’, guest curated by the art historian Alex Bacon. Tabouret, in particular, is becoming increasingly popular on both the primary and secondary market, with her perturbing figurative paintings often selling for six-figures. In the ‘20th Century Evening Sale’ this March, Christie’s in London sold The Last Day (2016) for £622,500, a green-tinged large-scale canvas depicting a school group of children in fancy dress, tripling the already generous estimate of £150,000-200,000.

© Claire Tabouret. Courtesy of the artist and Christie’s Images Ltd.

© Claire Tabouret. Courtesy of the artist and Christie’s Images Ltd.

Figgis too has become a reliable market figure, with her work consistently selling above estimate at auction. Rebekah Bowling, Head of the Contemporary Art Day Sale at Phillips, noted in an interview with Angelica Villa from Art Market Monitor that the demand for Figgis’s work at auction started to rise after the successful Hong Kong sale of The Birth of Venus (After Alexandre Cabanel) (2018) for HK$2.375 million in November 2019, which vastly exceeded their estimate of HK$250,000-400,000. Villa also reported that a month later, in December 2019, Figgis’s painting King and Queen (2015) sold at Sotheby’s in London for £52,500 against a low estimate of £4,000-6,000. In February 2020, Christie’s in London sold 17th Century Family (2018) for £125,000, while down the road at Sotheby’s, her Boat Trip (2017) had brought in £81,250. Both sales were respectively five and four times their estimate of £20,000-30,000. Despite the disruptive impact of Covid-19 on the market worldwide, Figgis’s rate has continued to accelerate. In July 2020, Phillips in New York sold Sunday Ladies (2017) for $125,000, exceeding the estimate of $50,000-70,000, and in December 2020, Wedding Party (2019) was sold at Phillips in Hong Kong for HK$4.4 million, mightily exceeding the estimate of HK$550,000-850,000.

Figgis plays with the hallmarks of traditional painting and it’s typical characters, therefore fulfilling both the market interest in the medium of painting and the desire for work that ruptures the tradition of art history.

Bowling had commented to Art Market Monitor that it was the “interpretations of art historical masterpieces” by Figgis which had achieved “the most robust results’’ at auction. Her work is inspired by famous painters, including François Boucher, Hans Holbein, James Ensor, Jean-Honoré Fragonard, and Diego Velázquez. Sometimes the homage is direct, with the original image replicated in her idiosyncratic off-kilter and slightly surreal style, such as in The Swing (after Fragonard) (2014) or Olympia (after Édouard Manet) (2018). In Ladies Picnic (Déjeuner sur l’herbe) (2014), she rejected Manet’s original representation of a naked woman picnicking with two dressed men, instead depicting four ghoulish ladies in ornate garb enjoying a cream tea on the lawn. While the image is witty, the provocation is polite, and the perceived feminism remains moderate enough to be accessible to a wide collectorship. Figgis’s practice more broadly riffs on aristocratic social portraiture, often portraying the luxurious and frivolous activities of the bourgeoisie. Her poking of the upper classes is enhanced by her interest in theatrics and the macabre, playfully transforming the refined life of the leisure class into something grotesque or overtly sexualised. The uncanny faces of her protagonists might appear congealed or contorted, with their limbs petering off into tendrils, or their bodies blurring with their environment.

Beyond the art world, Figgis’s candy-coloured palette was cited as influencing the pastel hues of Marc Jacobs’ SS19 runway. And, last year, in an interview with The Cut, Ellen Mirojtnick, the costume designer of Netflix series Bridgerton, noted that “the single artist that was the inspiration for [the show] was [Figgis]. I looked at her paintings and they just knocked me out.” Mirojtnick also commented that her costumes rebelliously mish-mashed historical periods, which is the approach that Figgis takes, converging Rococo romanticism with references to Gothic fairy tales, or mixing up the Baroque with Impressionism. The popularity of Figgis’s work has also coincided with a turn to hyper-femininity in women’s fashion, epitomised by the maximalist garments made by designers like Batsheva, Molly Goddard, and Simone Rocha. Heritage and tradition are ripped up and reformed. Despite their use of decorative elements, such as embellished puff sleeves or triple layers of frou-frou tulle, this style of clothing is designed for the bold and empowered woman, shedding any sartorial associations with female acquiescence.

Genieve Figgis paints women indulging in bawdy and pleasurable activities, in a riposte to the image of the passive woman replicated throughout male-centred art history.

Figgis has commented that she is influenced by fellow contemporary painters, citing in particular her admiration for Cecily Brown, Jenny Saville, and Dana Schutz. In an interview with Ben Eastham for Artsy, she noted that this specific group were dedicated to creating “figurative works that were not the traditional likeness of a sitter, but rather revealed the experimental nature of the artist’s journey with the figure.” The notion of an artist ‘balancing between figuration and abstraction’ is a phrase regularly touted in relation to this current generation of painters. Last year, Brown and Schutz were shown together in ‘Radical Figures’ at the Whitechapel Gallery in London; a survey exhibition that brought together a new generation of artists “revitalising the expressive potential of figuration”. In December 2020, Schutz’s Elevator (2017) sold for HK$50 million at the Christie’s ‘20th Century: Hong Kong to New York’ sale. Not everyone is a fan – in an article for The Spectator, critic Dean Kissick referenced the sale as part of his lambasting of the ‘zombie figuration’ trend, which he sees as “all stylistic gimmicks and new ways of remaking the classics”, chalking up the market success of certain artists being down to their creation of “Instagram-friendly cultural objects” that read “less like stylistic innovations and more like branding exercises”.

Brown’s work sells for millions on both the primary and secondary market, and she is now one of the highest selling female artists in the world. Her auction record is $6.7 million. In May 2020, Gagosian sold her painting Figures in a Landscape 1 (2001) for $5.5 million through its online viewing platform. Like Figgis, Brown also blends allusions to art history into her paintings, albeit less directly, referencing a variety of figures from Titian, Peter Paul Rubens, and Edgar Degas to Willem de Kooning and Francis Bacon. In the promotional video for the sale, Gagosian director Deborah McLeod pointed out that the prices of work made by Brown’s inspirations are now out of reach for most collectors, but that her painting manages to embody their storied trajectories: “[it is] an iconic masterpiece that looks back in dialogue with our history and will hold up for generations to come”. Both Brown and Figgis’s works are desirable because they manage to pay homage to the majestic art of the past while still maintaining their own originality and cutting-edge contemporary appeal.

© Cecily Brown. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery.

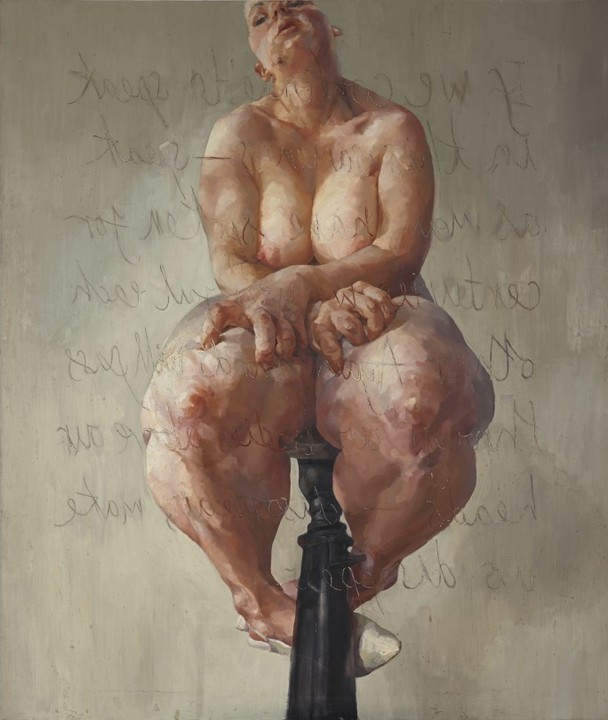

Figgis paints women indulging in bawdy and pleasurable activities, in a riposte to the image of the passive woman replicated throughout male-centred art history. Their carnivalesque appearance and abject behaviour is a provocation to normative ideals. Like Saville, who she reveres, the reclaiming of a bold female subjectivity is adopted as a means to shift the role of power. Saville is best known for her large-scale, uncompromising oil paintings of fleshy, corpulent female figures. In 2018, her nude self-portrait Propped (1992), sold at Sotheby’s in London for £9.5 million against an estimate of £3-4 million.

© Jenny Saville. Courtesy the artist and Sotheby’s.

The market ascent of these female artists is consistent with the drive occurring in museums to diversify and expand the parameters of art history, placing new emphasis on non-white and non-Western artists, in addition to women artists marginalised by their peers, for example, the recent glut of shows looking at female Surrealist or Abstract Expressionist artists. The power of institutional change has in turn influenced collectors to look beyond their usual remit, hopefully transforming the market into a more representative realm.

-min.jpeg)