On Photography and Black Representation

For hundreds of years, Black subjects in paintings were portrayed in stereotypical ways until the popularisation of photography allowed for Black communities to regain control of their representation. Tracing the fraught racial history of the medium, we highlight the contemporary Black photographers who have returned to photography to investigate its ability to empower and represent its subjects.

In 1634, Flemish painter Justus Suttermans was commissioned to paint three members of the Medici household. Two were old female servants and the third was a Black enslaved man named Pietro who was tied financially and legally to his aristocratic owners. While the two women — Domenica delle Cascine and Cecca di Pratolino — look convivially at each other, Pietro lingers in the background, unsure and somewhat sullen about his role in the painting.

Edward Poynter, The Visit of the Queen of Sheba to King Solomon, 1890 (Oil on canvas), Art Gallery of New South Wales

For hundreds of years, Black subjects in paintings were portrayed in stereotypical ways. Renaissance paintings often exoticized Black subjects, while many works from the 18th and 19th centuries solely depicted them as enslaved people. When the historical subject of a painting should have been Black, as was the case with Edward Poynter’s “The Visit of the Queen of Sheba to King Solomon,” artists often chose to replace them with someone with fairer skin.

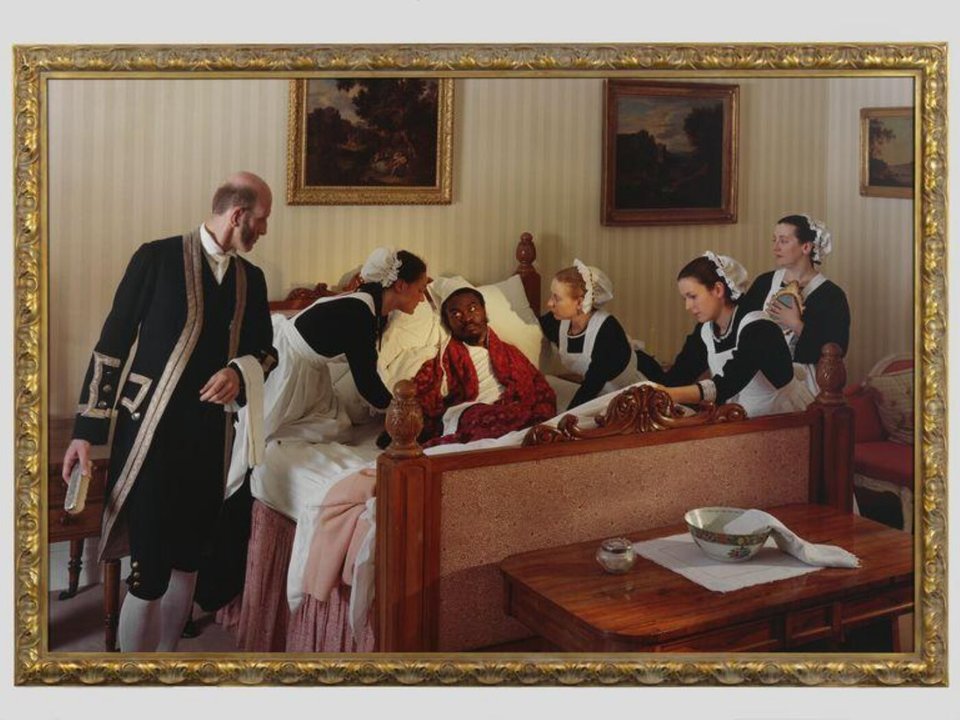

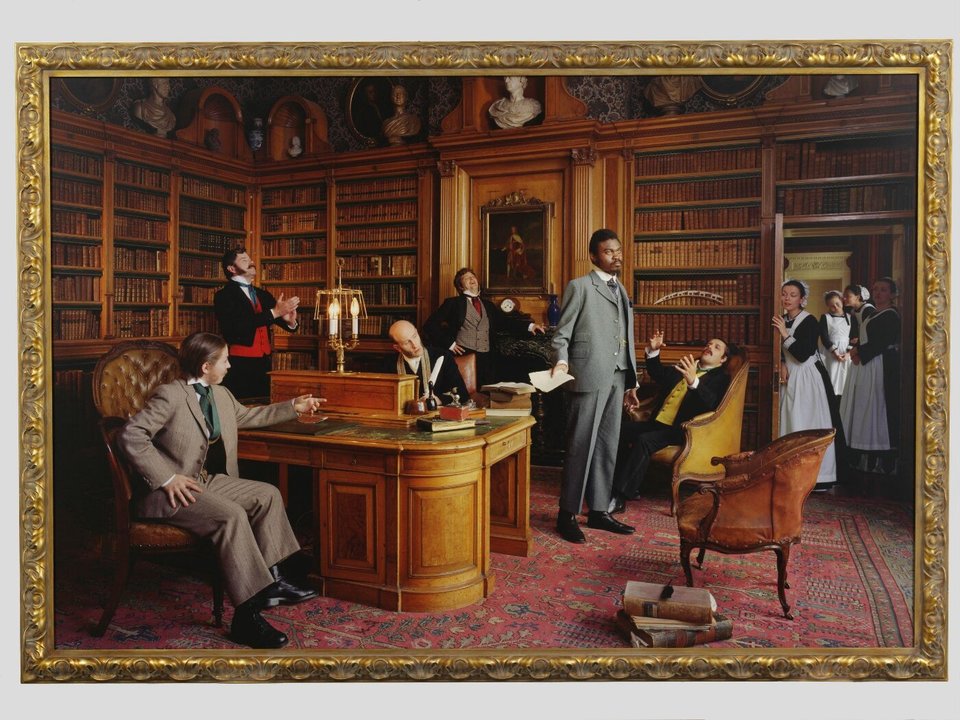

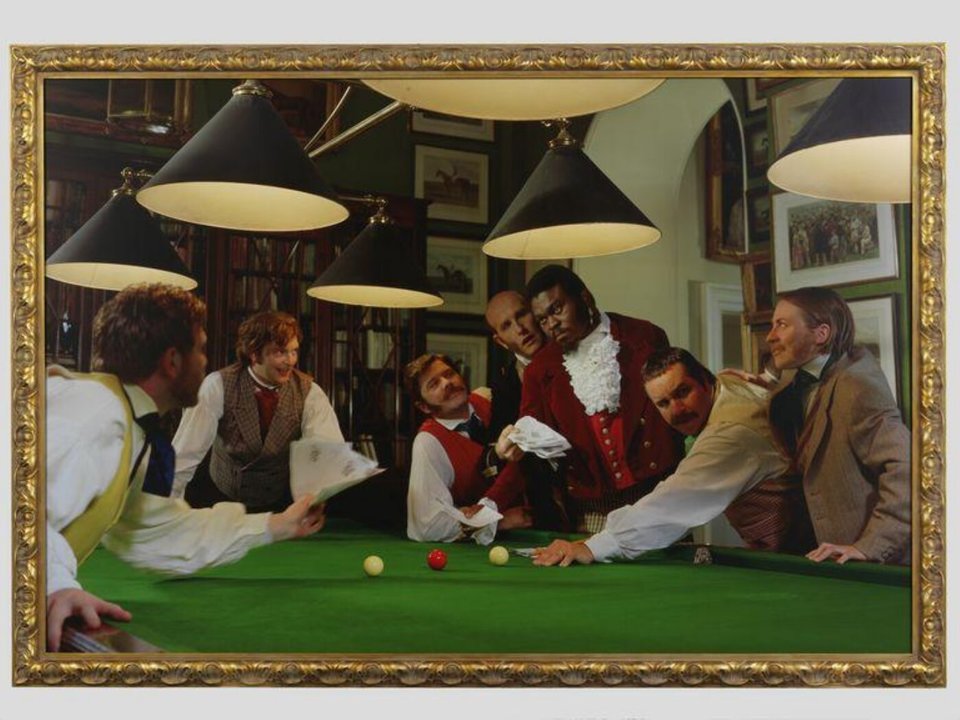

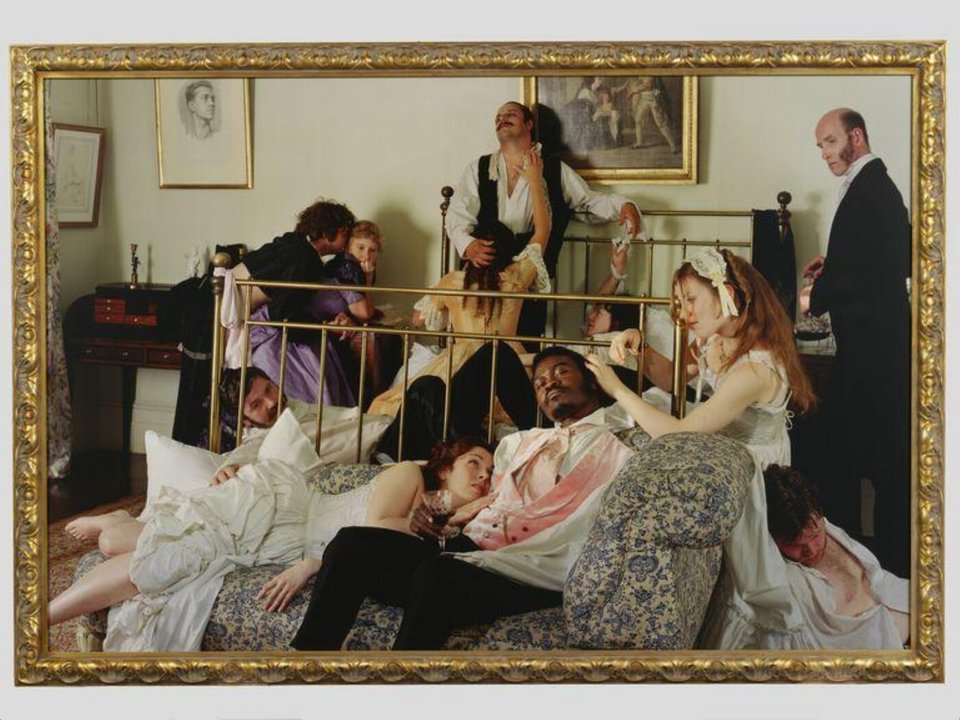

In his Diary of a Victorian Dandy series, Shonibare reimagines 18th century paintings with Black protagonists, offering an alternative history where Black subjects controlled their representation.

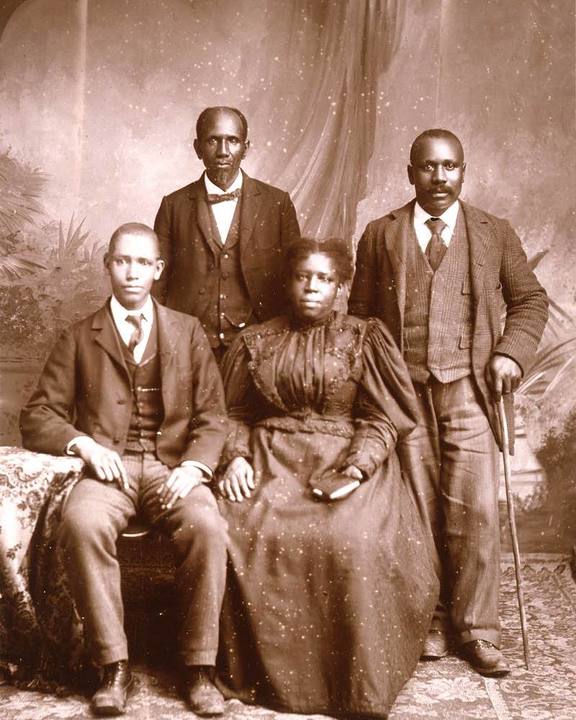

In the United States, as Black communities began to gain autonomy following the Civil War, some started searching for ways to represent themselves visually on their own terms. Photography became a preferred medium because of its ability to realistically depict subjects, as well as its relative affordability. For Black communities, it became a way to regain control of their representation, both in art and in popular culture.

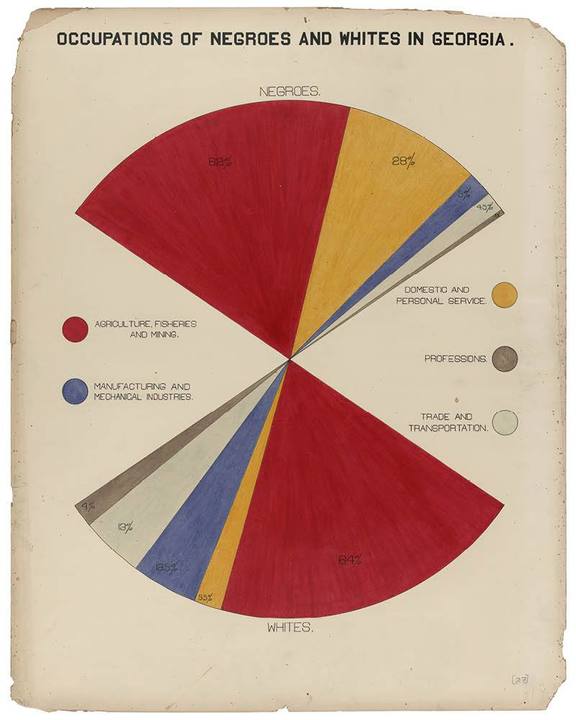

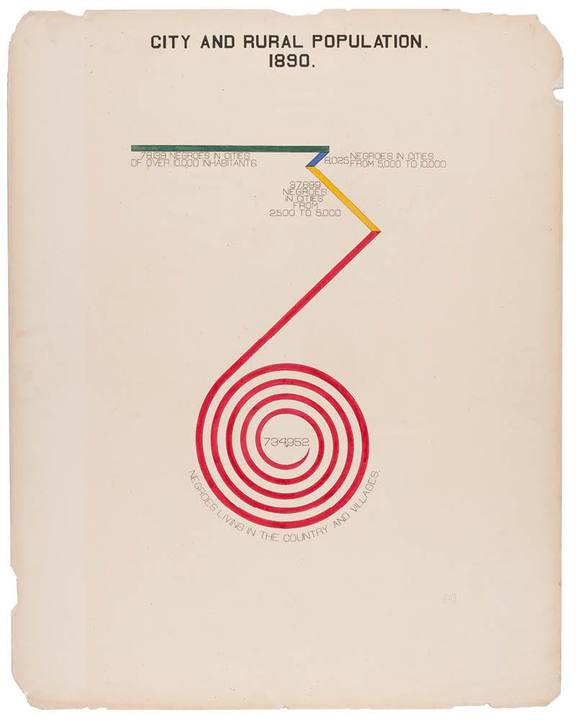

During the years following emancipation, nearly every large Black community had a local photography studio. At its peak, there were at least 50 Black daguerreotypists working in the US. Black thinkers saw photography as an affordable means of disseminating their image and, by extension, their message. Frederick Douglass announced a goal to become the most-photographed man of the 19th century. He succeeded. When W.E.B Du Bois was asked to curate an exhibition for the 1900 Paris Exhibition, he chose photography as a way to contest the prevailing image of “Negro criminality,” which had been used to legitimize lynchings by showing Black subjects as inherently guilty.

Of course, photography was also used to perpetuate racism — the medium’s affordability and low barrier to entry allowed for photographs of lynchings to be reproduced on postcards and disseminated widely in the US throughout the 19th century. These postcards subsequently helped normalize lynchings during the Jim Crow era and contributed to the spread of the practice across the country. More recently, artists have started to take a critical approach to photography’s darkest moments. In his Erased Lynchings series, Ken Gonzales-Day reflects on the heartless nature of these atrocities by removing the subjects of the photographs. As a result, he removes the exploitative focus on the victim, zeroing in on the crowd and their complacency.

During the years following emancipation, nearly every large Black community had a local photography studio. Black thinkers saw photography as an affordable means of disseminating their image and, by extension, their message.

Contemporary Black photographers have returned to the core components of photography to investigate the medium’s ability to empower and represent its subjects. Yinka Shonibare’s work spans a variety of mediums, almost always focusing on African identity in the diaspora. In his Diary of a Victorian Dandy series, Shonibare reimagines 18th century paintings with Black protagonists. Shonibare’s dandy, played by himself, is Black — he places himself at the centre of the elaborately composed photographs, offering an alternative history where Black subjects controlled their representation.

Shonibare’s photographs bear a strong connection to British painter William Hogarth’s The Rake’s Progress, a satirical series of engravings detailing the life of a wealthy and hedonistic man of leisure. Reflecting a broader norm in 18th century England, Hogarth made ample use of racial imagery in his satire, turning his Black subjects into dehumanized objects of humour. Like Hogarth’s series, Shonibare’s work chronicles the moral decline of the dandy but he has reversed the “otherness” of Blackness that formed the core of Hogarth’s racial satire. The dandy is now a multi-layered figure in a way that Black characters were never allowed to be in Hogarth’s work.

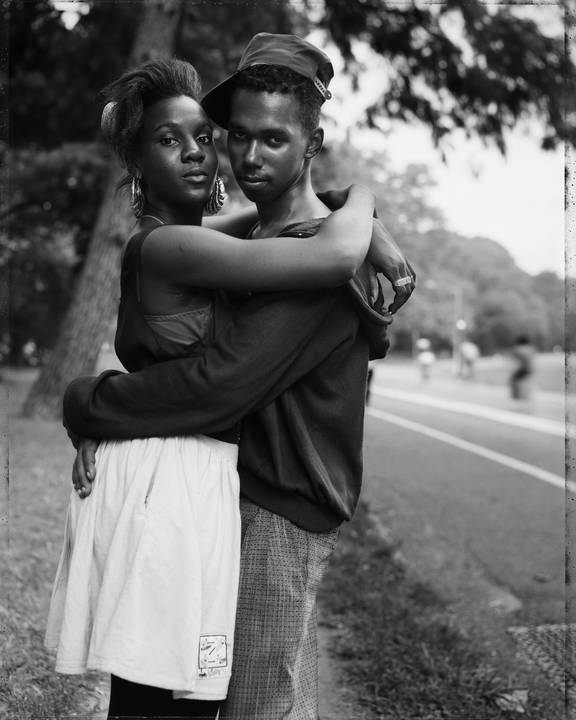

For Dawoud Bey, photography is also a way to present a complex representation of Black subjects. Bey first gained recognition with his black-and-white portraits of people on the streets in Harlem, Manhattan’s famous historically Black neighbourhood. With an eye toward the long history of artists exploiting their subjects, Bey recognized photography’s unique ability to empower its subjects. Initially, he worked with a Polaroid positive-negative film so he could give subjects a print of themselves, fostering a more reciprocal relationship. In his Street Portraits series, Bey used a large format camera that required him to take photographs slowly, allowing him to spend more time with his subjects.

Dawoud Bey, Street Portraits, 2021, Courtesy MACK. © Dawoud Bey

Over his more than thirty-year career, Bey has become known as one of the foremost portrait photographers in the art world. He has a national presence and substantial cultural recognition, according to Limna’s analysis of his career. Later, he would go on to experiment with diptychs and triptychs that combine multiple photographs into one, and write prompts for his subjects that he would display alongside their portraits. The resulting photographs of Black men and women, as well as a variety of other people, share a warmth and complexity that allow his subjects’ humanity and autonomy to shine through.

Contemporary Black photographers have returned to the core components of photography to investigate the medium’s ability to empower and represent its subjects.

Paul Mpagi Sepuya takes a much more literal approach to representation, using mirrors and the bodies of himself and his friends to understand how photography conceives of and visualizes both race and sexuality. While his career is still nascent compared to Bey and Shonibare, Limna ranks Sepuya high on cultural recognition and suggests that he has a strong career momentum. In his photographs, arms appear to emerge from boxes, bodies are disconnected from their faces, forcing us to reckon with the way that the photographic medium represents and objectifies the bodies of Black and queer subjects.

-2017.jpeg)

_2020.jpeg)

_2019.jpeg)

-2020.jpg)

-2017.jpeg)

Sepuya’s photographs are, at their core, studio portraits, albeit not in the traditional sense. His works are more focused on breaking down the structures of the space, rather than upholding them. He often depicts subjects against backdrops where the edges are visible, revealing the constructed nature of the photograph.

This kind of self-conscious representation harkens back to the earliest days of photography in Black communities, where the subjects saw the medium as a self-directed means of representation. Sepuya will also often capture himself in a mirror in front of his camera, so that the lens is pointing directly at the viewer. By placing us in front of the camera, we are forced to examine our own attempts at forming identity using their body — how we hold ourselves, and what that expresses to others.

-min.jpeg)