Painting a thousand words: the ever-changing appeal of text-based art

Text-based art has always been a vibrant sign of the times. Today, as words and images collide more than ever, we trace the artistic tradition of combining the visual and the textual, and outline its evolution in tandem with media and technology.

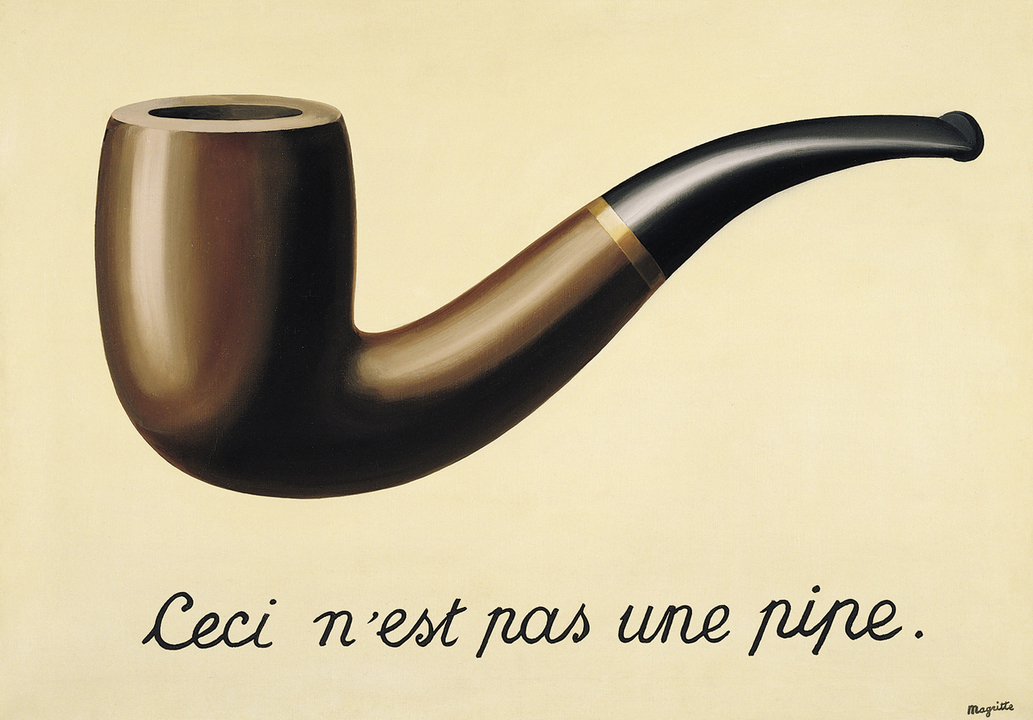

“Ceci n’est pas une pipe”, reads the infamous cursive text beneath René Magritte’s picture of a smoker’s pipe. Presented like an advertisement, with the pipe as the product and the text as the slogan, the ability of ‘The Treachery of Images’ (1929) to provoke philosophical debate has proved boundless. For almost a century, the painting has been held up as a treatise on the impossibility of reconciling word, image and object – inviting viewers to think twice about the messages they’re confronted.

René Magritte’s “The Treachery of Images”, 1929

“It gets you to stop short,” says art historian Emily Hage. “It makes you question what you’re looking at, which is maybe why it’s so relevant to people today, because we’re bombarded with images and words all the time. You really do need to have a critical cap on, to stop and say, this is not a pipe, it’s a picture of a pipe. What’s going on here?”

Magritte’s pipe participates in an expansive tradition of combining the visual and the textual in art, one which has evolved in tandem with media and technology, and is finding new audiences and new forms as words and images collide more than ever today.

It makes you question what you’re looking at, which is maybe why it’s so relevant to people today, because we’re bombarded with images and words all the time.

Stretching back to medieval manuscripts and the illuminated works of 18th-century poet William Blake, text-based practices reached fever pitch with the fragmented sound poetry and nonsense collages of the Dadaists during the First World War. Born out of a distrust of language and rationality, Dadaism’s ground-breaking experimentations laid the foundations for the spoken-word performances of the Fluxus movement in the 1960s, while text as art object similarly became a hallmark of the Conceptual movement, which emphasised ideas over visual elements.

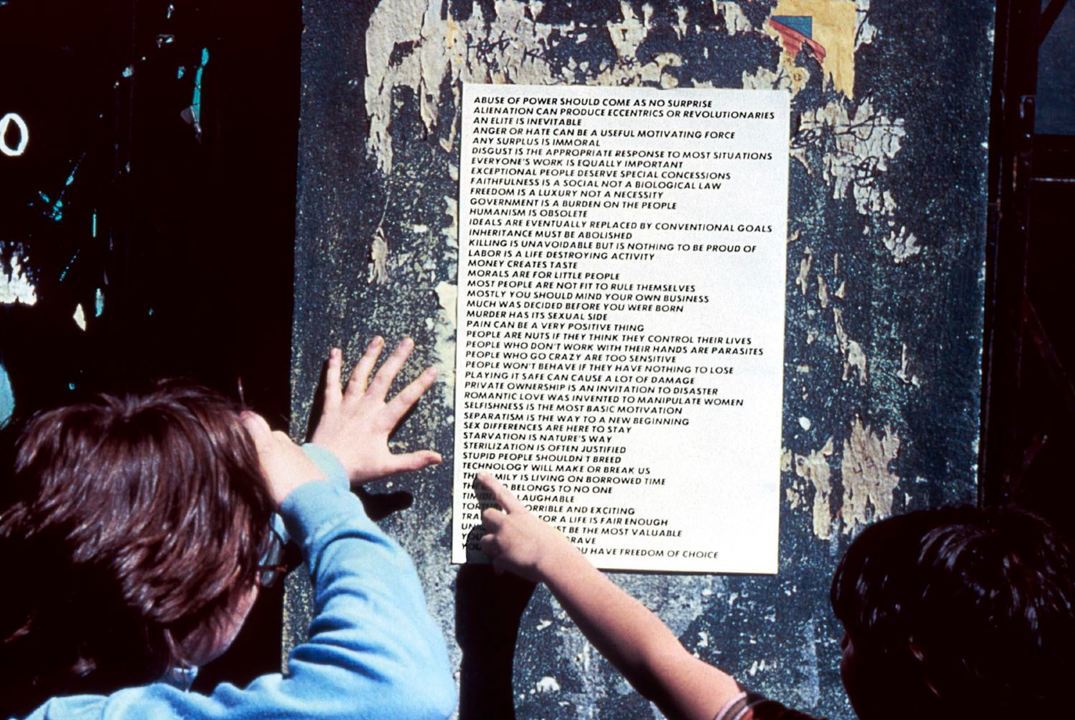

If Magritte’s pipe has only grown more relevant with age, so too has the work of American conceptual artist Jenny Holzer (b. 1950). Alongside artists like Barbara Kruger (b. 1945), who subverts the messages of mass media and advertising, Holzer turns words into visual spectacle and troubles the line between meaning and misunderstanding. It all began with her Truisms (1977-79), a series of more than 250 single-sentence declarations created while she was studying at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art. These pithy one-liners were distilled from the books on her reading list, and pivoted from the vulnerable to the aggressive to the comic: “Categorizing fear is calming”; “Abuse of power comes as no surprise”; “A lot of professionals are crackpots”; “Money creates taste”.

After hand-typing and printing her sentences, Holzer anonymously wheat-pasted them to buildings, walls and fences across New York. Passers-by were confronted with statements that read like unassailable truths, but were riddled with paradoxes when taken collectively, thereby resisting easy interpretation. “From the beginning,” Holzer explained in 1985, “my work has been designed to be stumbled across in the course of a person’s daily life. I think it has the most impact when someone is just walking along, not thinking about anything in particular, and then finds these unusual statements either on a poster or in a sign.”

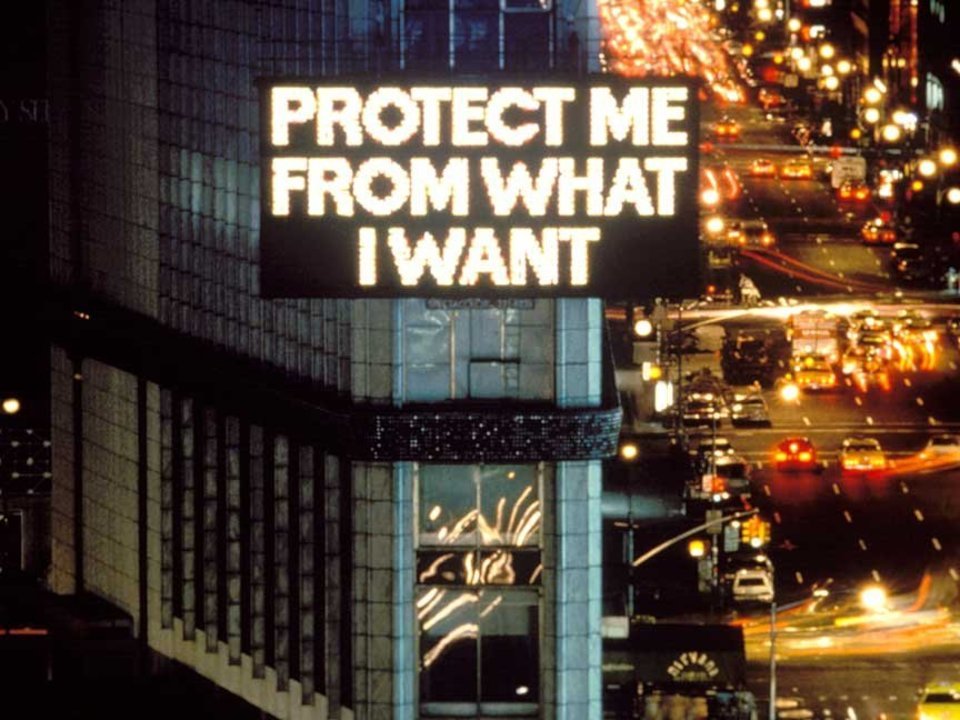

Holzer’s democratic delivery of words and ideas in public spaces developed alongside technology. In 1982, her ‘Truisms’ flashed down at New Yorkers in LED lights from the electronic Spectacolor board in Times Square, igniting a career-spanning series of light projections on buildings and landscape. In 2021, Holzer took over the Guggenheim in Bilbao with her exhibition ‘Like Beauty in Flames’, during which she presented her thought-provoking statements through the medium of augmented reality.

The exhibition consisted of two site-specific augmented reality works, in which her words interacted with the Guggenheim’s architecture, while an accompanying app enabled users to project her ‘Truisms’ onto their own environments anywhere in the world. (Kruger will similarly be taking over a building this spring, addressing disputes on internet forums via a written installation at Berlin’s Neue Nationalgalerie.)

Social media has conditioned the eye – and our attention spans – to value concise, beautifully presented text, tightly-packed with meaning.

As the technologies surrounding Holzer’s work have changed, so too has our appreciation of it. Not only do we randomly stumble across opinions more perplexing than her ‘Truisms’ every time we open our phones, but social media has also conditioned the eye – and our attention spans – to value concise, beautifully presented text, tightly-packed with meaning.

As Holzer told the New York Times in 1989: “In the ‘Truisms’, I wanted to write clichés and I was successful. You only have a few seconds to catch people, so you can’t do long, reasoned arguments.” If audiences only had a few seconds to be “caught” back in the 1980s, it’s milliseconds now. As such, her LED-lit profundities have experienced something of a renaissance on Instagram feeds in recent years.

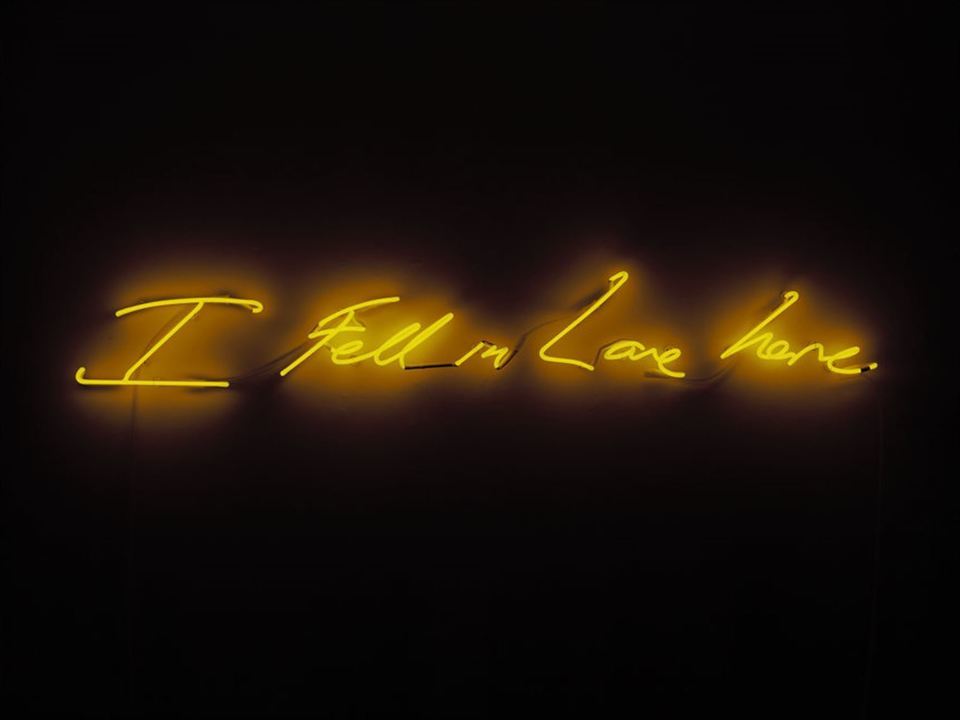

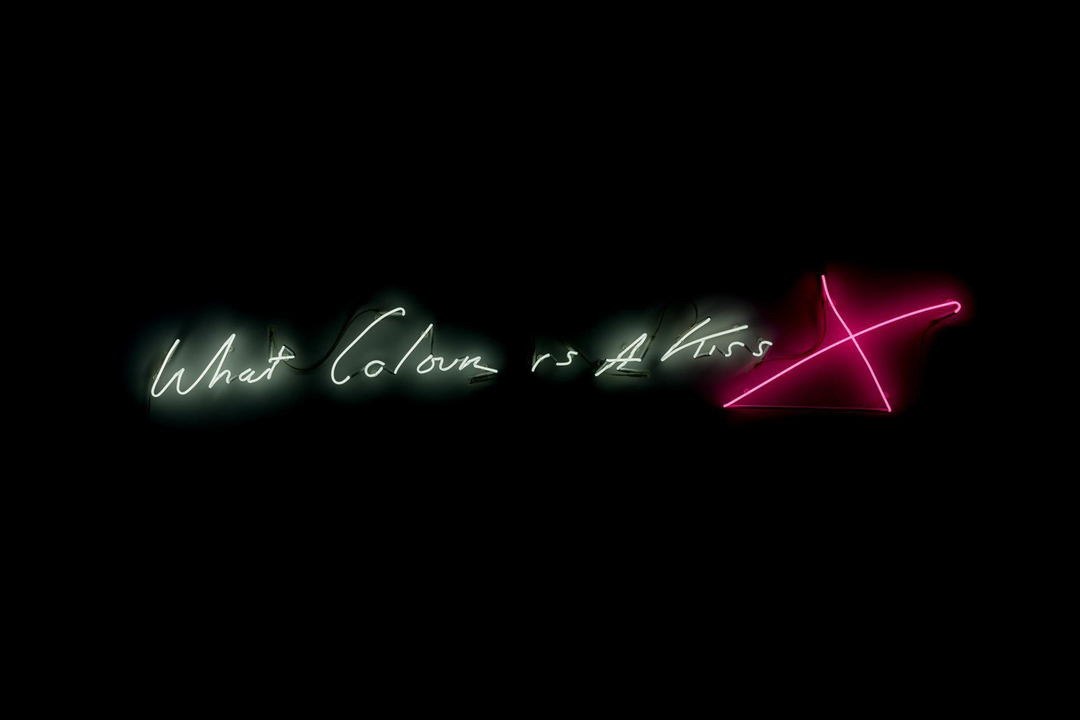

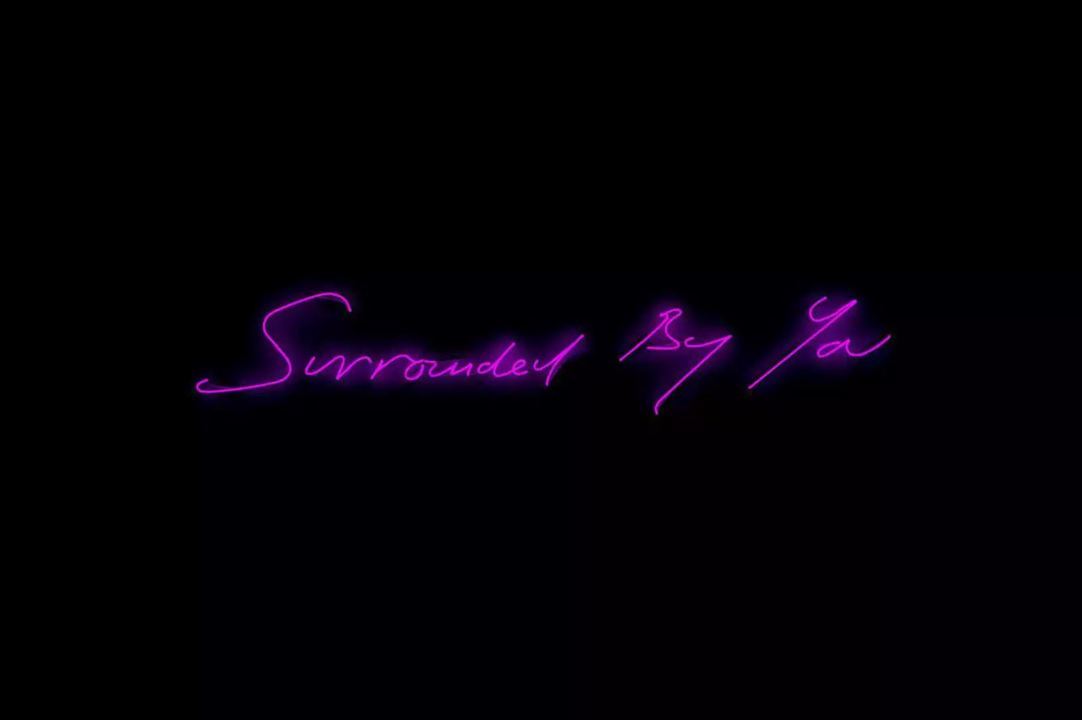

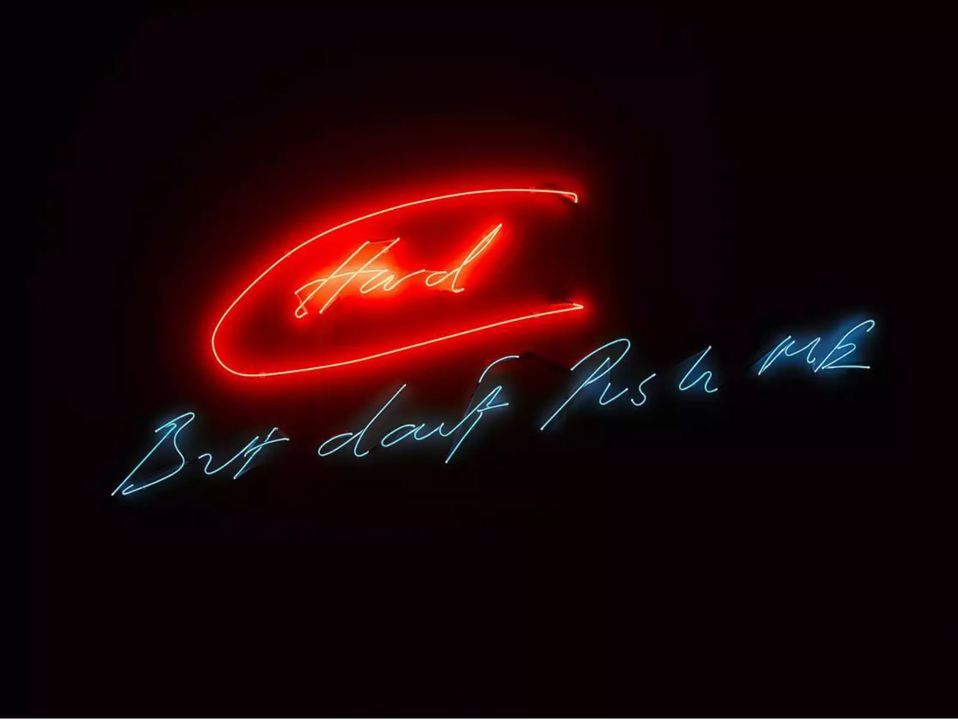

Social media has also given new context and currency to confessional art, such as the neon signs of British artist Tracey Emin. Emin began working with neon gaslights in the early 1990s, using the industrial medium in a diaristic manner to memorialise fleeting thoughts and desires. Scribbled in her handwriting, her romantic outpourings feel deeply personal but also abstract enough to pertain to each individual viewer.

At once candid and clichéd, phrases like “I fell in love here”, “I woke up wanting to kiss you”, and “What Colour is a Kiss” reach towards something fundamental. In the era of the first-person industrial complex, in which we’re encouraged to document our every musing and memory, naked confessionalism like Emin’s feels right at home – there’s a desire for authenticity online, even though the process of self-presentation is often devoid of it.

Text-based art demands more from the viewer than the purely visual; whether you’re reflecting on the provocations of Holzer or indulging in the romanticism of Emin, there’s a degree of interactivity to the process of reading that goes further than letting your gaze linger on a painting. Contemporary British artist Helen Cammock harnesses this exchange, constructing intersectional dialogues and inviting her viewers to participate.

As part of her 2017 multimedia exhibition, Shouting in Whispers, Cammock produced a series of monochrome posters, each bearing sparsely printed statements wrought with feeling. Some are authored by Cammock herself, others – “This is not a love song”; “Evocation is a mutual emotion” – are quotes from writers, poets and activists.

“Part of my intent in all of my work circles around empathic engagement between voices; from the different voices in the projects to the relationships that emerge with the audience. My work is about the weaving together of stories,” the Turner Prize-winning artist has said. Motivated by her commitment to questioning mainstream representations of Blackness, womanhood, wealth, power, poverty and vulnerability, Cammock’s narratives are multi-layered and non-linear, engaging viewers on personal and political levels.

The practice of combining word and image is an agile one… From critiques of information overload to the renewed appeal of the confessional, text-based art continues to be a vibrant sign of the times.

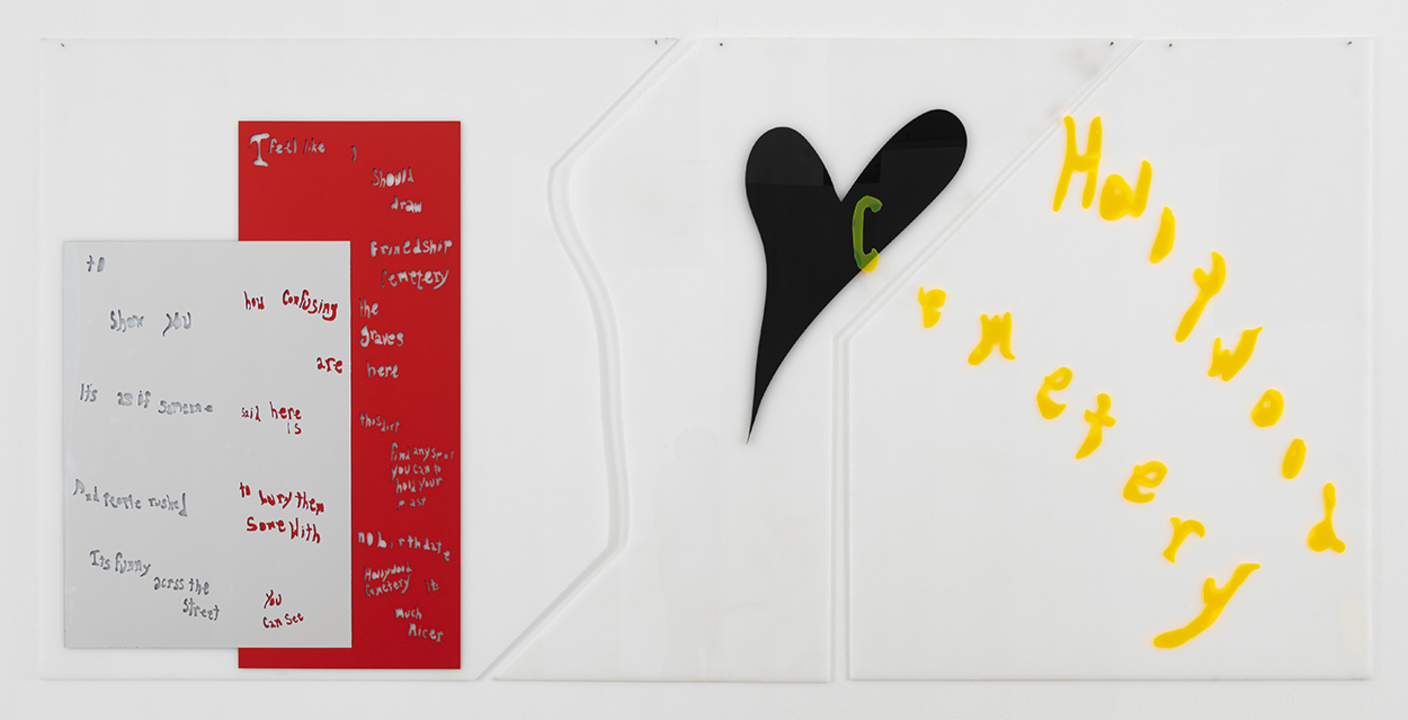

These verbal-visual practices are being continuously updated by emerging artists today. Raque Ford, a Brooklyn-based artist with a climbing presence according to Limna, draws intimate feelings into the public realm by carving textual fragments into hard surfaces like acrylic. In doing so, she gives narrative and material form to abstract thoughts and emotions. Her inscriptions are scraps of conversation and song lyrics, snippets of fiction and personal notes. Ruminating on themes of grief, ancestry, and love, two works created last year, ‘Hollywood Cemetery (I The Fool)’ and ‘Friendship Cemetery (The Wise)’, are on view at MoMA PS1, as part of the group show, ‘Greater New York 2021’, through April 18.

Raque Ford, “Friendship Cemetery” (The Wise), 2021

Raque Ford, “Friendship Cemetery” (The Wise), 2021

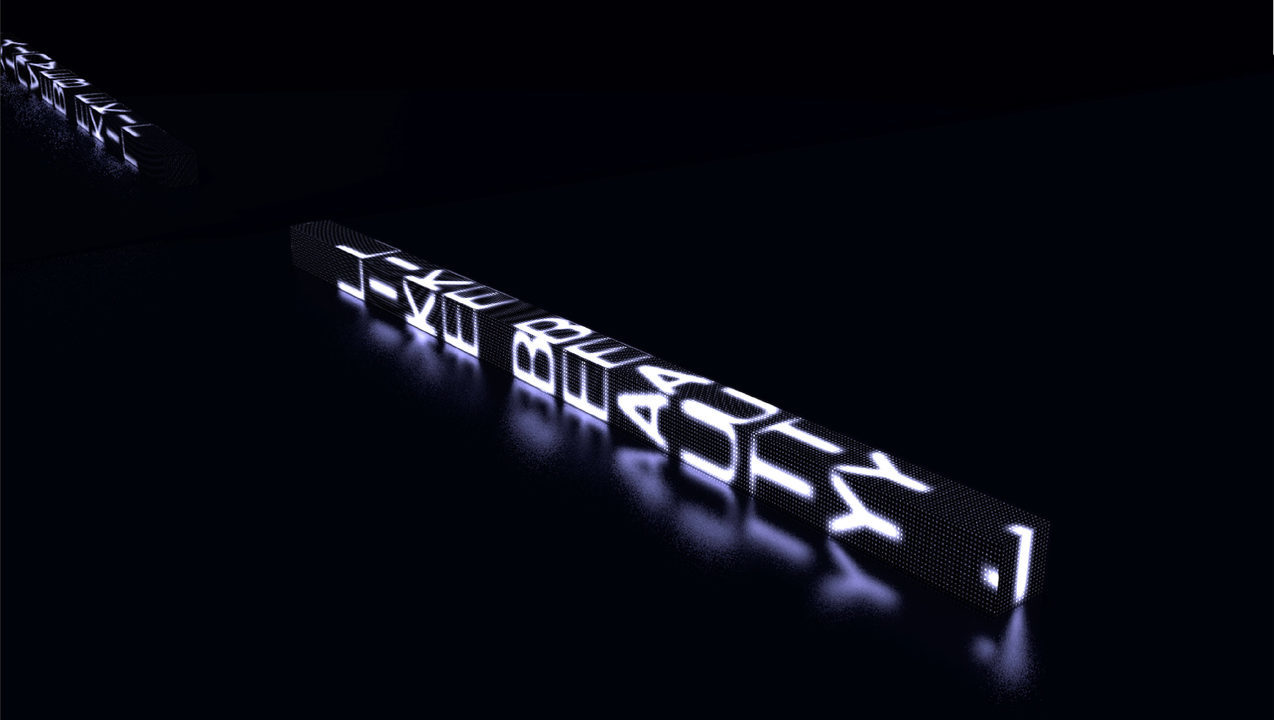

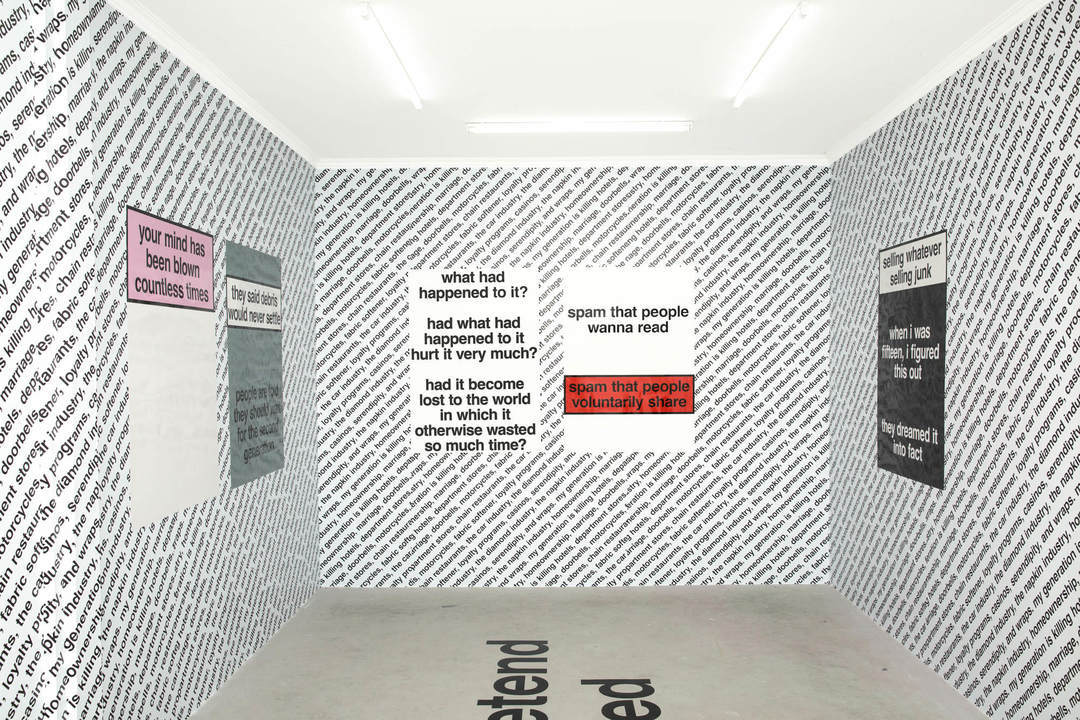

Croatian-born Amsterdam-based artist Nora Turato, who has a rapidly climbing international presence according to Limna, similarly incorporates found text from contemporary culture into her practice. Turato evokes the topsy-turvy methods of the Dadaists in her attempt to expose the volatility of language, absorbing information from her smartphone, advertisements and everyday conversations, and reassembling it into linguistic-visual scripts for videos, installations, art books and spoken word performances. In merging political statements with Kardashian quotes, marketing jargon with wellness affirmations, there’s a playfulness to her multidisciplinary approach that doesn’t detract from its urgency. Her work is also on show at MoMA this March, and at Kunsthaus Hamburg from March to May.

The practice of combining word and image is an agile one, whether it’s finding fresh expression at the hands of ultra-contemporary artists, or, in the case of blue chip artists like Holzer and Kruger, being updated and appreciated anew. From critiques of information overload to the renewed appeal of the confessional, text-based art continues to be a vibrant sign of the times.

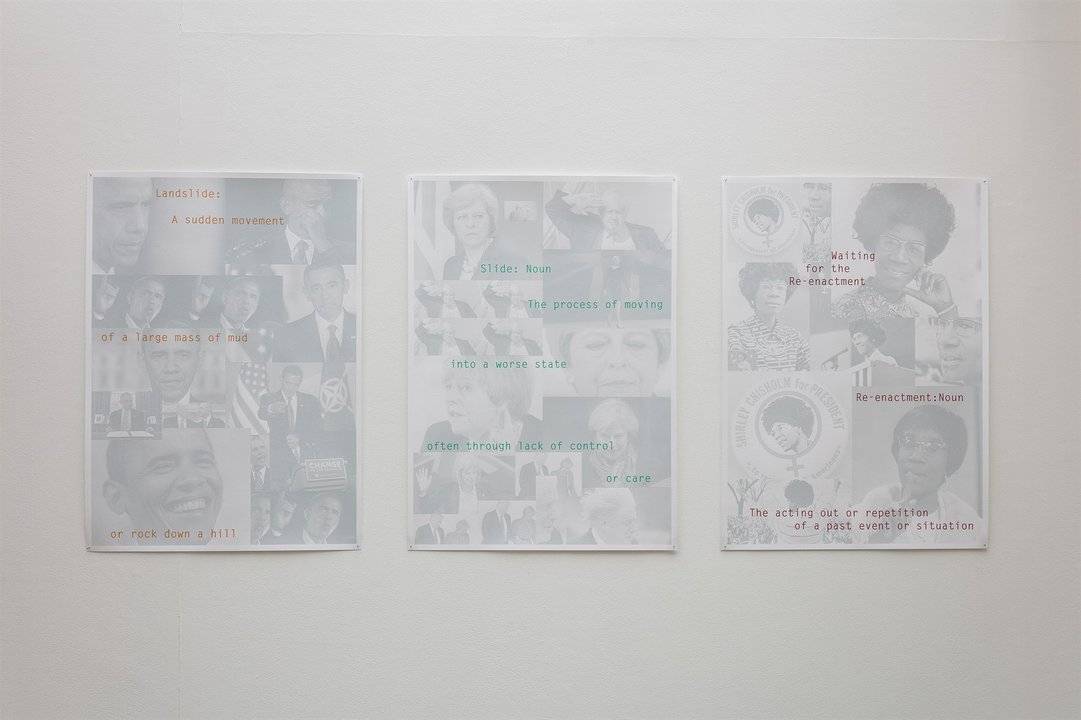

Nora Turato, “A Festival of Consent”, exhibition view, LambdaLambdaLambda, Prishtina, 2018.

Nora Turato, “A Festival of Consent”, exhibition view, LambdaLambdaLambda, Prishtina, 2018.

Nora Turato, “don’t tell me where this is going, i loooo-ooooo-ooove surpris-es”, exhibition view, LambdaLambdaLambda, Prishtina, 2021

Nora Turato, “don’t tell me where this is going, i loooo-ooooo-ooove surpris-es”, exhibition view, LambdaLambdaLambda, Prishtina, 2021

-min.jpeg)