Queering the classics: a new vision for the old masters

As the old masters canon seems increasingly removed from the present, how do institutions make old works by predominantly all-white and all-male painters appeal to the new world? For New York’s Frick, the answer lies in working with contemporary artists to reinterpret the gender politics previously excluded from narratives of early modern art.

In 2020, Robin Pogrebin of the New York Times asked, “Can the old masters be relevant again?” In her article, she questioned whether the works of the old masters would retain their coveted status in auction houses, galleries and museums with the art market so focussed on breaking new ground and satisfying appetites for the contemporary. Pogrebin cited shrinking inventories and dwindling profits in the old master category, which generally denotes those fully-trained, highly-skilled artists working in Europe in the period after the Renaissance up until 1800, from Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael and Caravaggio to Rembrandt, Vermeer and Jan Brueghel the Elder.

As institutions attempt to diversify and attract wider and younger audiences, spotlighting the predominantly all-white, all-male old masters canon seems at a remove from the demands of the present.

The market is still sluggish today: this year, Art Basel and UBS reported that sales of old masters have fallen in value by over 60% in a decade. While this is primarily down to the thin supply of high-quality works in circulation, the question of how to make the old masters appeal to the new world remains. As institutions attempt to diversify and attract wider and younger audiences, spotlighting the long-lauded work of the predominantly all-white, all-male old masters canon seems at a remove from the demands of the present.

For New York’s prestigious Frick, an institution devoted to European masterpieces from the Renaissance to the early twentieth century, an opportunity arose to explore this question in March of this year. As renovations continued at the grandiose Frick Collection (1913–1914), its permanent residence, the Frick moved its historic holdings into a temporary home in the Breuer building on Madison Avenue.

Every work of art is having a conversation with whoever is looking at it. The conversation continues to change as the viewer moves through time: every generation, geography and context will create a different perspective. - Aimee Ng, Frick curator

“When we opened at Frick Madison earlier this year, people began to see the collection in a new way,” says Frick Curator Aimee Ng. “We started to see a lot of people in this very modernist setting who’d never stepped foot in the Frick’s original home on 5th Avenue. But we also met contemporary artists who revealed that they’ve been studying paintings at the Frick for years and that it’s been inspiring their work.”

When major paintings in the Frick’s old master collection went on loan to shows internationally, Ng and Xavier F. Salomon, Deputy Director and Peter Jay Sharp Chief Curator, decided to fill the empty spaces with something different. “We thought, there are people out there who’ve been telling us that the Frick has been a source of inspiration for them, so why don’t we show this connection and inspiration on our very walls?” Ng explains. “It felt like the right opportunity to explore and almost experiment with our audiences and with our own collection.”

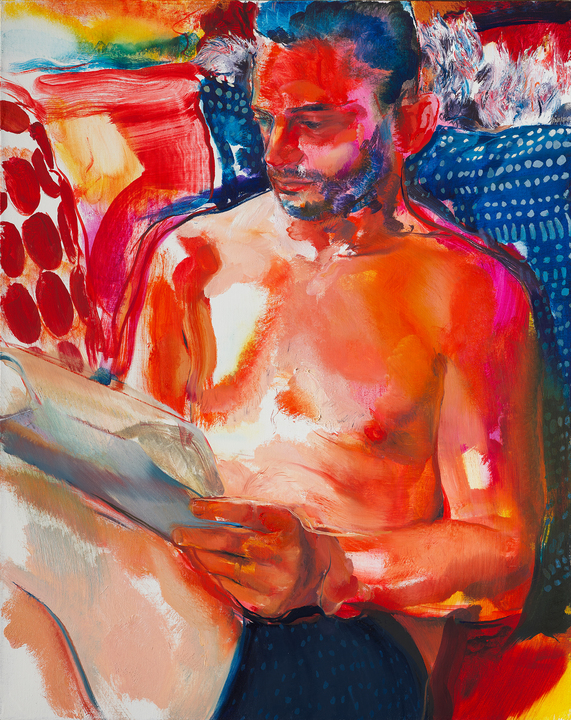

Together, Ng and Salomon curated the year-long pop-up exhibition Living Histories: Queer Views and Old Masters (Sept 2021 – August 2022), for which they commissioned four of those contemporary New York-based artists to each present a single new work in conversation with old master paintings in the Frick’s collection, with particular emphasis on issues of gender and queer identity typically excluded from narratives of early modern European art. Paintings by Doron Langberg (b. Israel, 1985) and Salman Toor (b. Pakistan, 1983) are currently on show, with Jenna Gribbon (b. USA, 1978) presenting her piece from January 2022, and Toyin Ojih Odutola (b. Nigeria, 1985) from April.

Xavier F. Salomon, Deputy Director and Peter Jay Sharp Chief Curator; Salman Toor; Aimee Ng, Curator; and Doron Langberg with Toor’s Museums Boys (2021) and Langberg’s Lover (2021) Photo: Joseph Coscia Jr.

Toor, a renowned mid-career artist with a rapidly climbing international presence according to Limna, is known for his tender, narratively-rich figurative paintings, which depict the lives of young, brown, queer men navigating diasporic identities and cosmopolitan culture. Toor’s ‘Museum Boys’ (2021) responds to the “quiet flirtations” in Dutch master Johannes Vermeer’s ‘Officer and Laughing Girl’ (c.1657) and ‘Mistress and Maid’ (c.1666−67). Tinged with an eerie phosphorescent glow, the imaginary allegorical scene in ‘Museum Boys’ portrays an encounter between a ghost-like figure and a dandyish half-naked man, the space between them occupied by a vitrine full of objects and limbs.

As Toor describes, his fragmented body parts and stone busts hint at “the fracturing experience of growing up as a femme boy in a macho, patriarchal culture and assimilating (to an extent) into western urban culture.” They are also a nod to the “objects from faraway” featured in Vermeer’s domestic settings, which were themselves a cipher for the 17th-century Dutch supremacy in global trade that transformed Toor’s home region of South East Asia.

Through the call-and-response format of the exhibition, Toor constructs queer and post-colonial critiques around Vermeer’s work. “With this proximity to the reverential world of the old masters, I want to question who the European history of painting, humanism, and empire belongs to,” he says. “I want to explore exciting new ways of connecting the past with the present.”

Opening up dialogues between contemporary and classic is also integral to the efforts of Christie’s Old Masters Department. “We recognise that going forward the market is going to be reliant on a new generation of collectors,” says Specialist and Head of Evening Sale Clementine Sinclair. She details the various initiatives undertaken by Christie’s to engage with younger collectors, from collaborating with Christie’s modern and contemporary departments for private selling exhibitions, such as 2018’s ‘Sacred Noise’, to including masterpieces like Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘Salvator Mundi’ in a post-war sale with a more expansive audience – a painting which fetched a record-breaking $450 million in 2017, the most expensive work ever sold at public auction.

Leonardo da Vinci, Salvator Mundi, c.1500, oil on walnut, 45.4 × 65.6 cm

In 2020, Christie’s asked German artist Volker Hermes to reinterpret a selection of pieces from their Classic Week auctions. As part of his Instagram-friendly ‘Hidden Portraits’ series, Hermes used Photoshop to obscure the faces of old master portraits, shifting the viewer’s attention towards the surrounding signifiers of identity: multiplied to excess, a glut of grapes covers the face of Christiaen van Couwenbergh’s (1604-1667) ‘Bacchus’, leaving only the god’s lips visible, while the face of Giusto Suttermans’s ‘Eleonora Gonzaga’ (1621) is masked with layers of ruffs except for her eyes, allowing her to peek at the viewer instead.

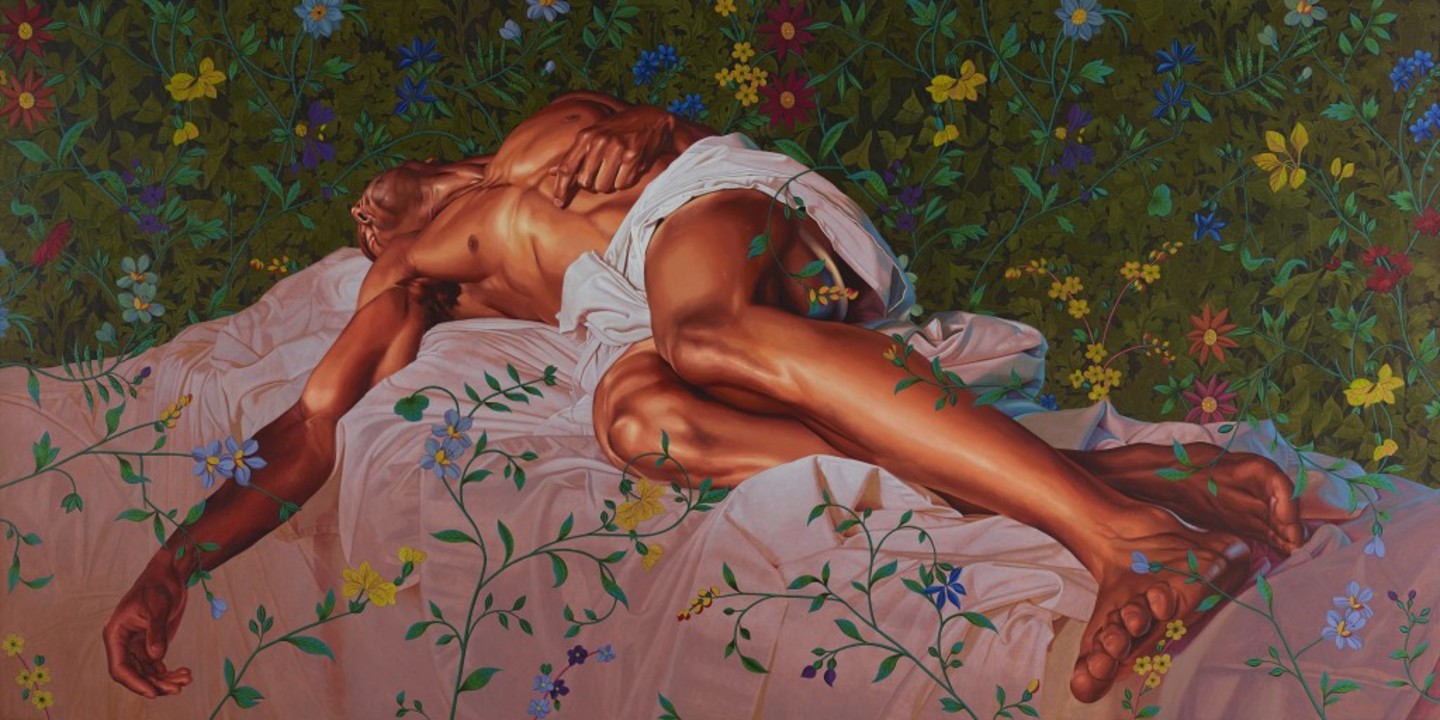

Darting between exaggeration and obfuscation, Hermes’ interventions encourage us to probe the power dynamics and gender norms painted into the old master originals. These themes are similarly interrogated by the likes of mid-career Swedish artist Arvida Byström, who plays on the symbolism of the Dutch still-life tradition as part of her exploration of femininity in digital culture, and mature New York-based artist Kehinde Wiley, who harnesses conventions of glorification in old master paintings to create heroic portraits of people of colour.

There is still new ground to be broken within the old master category itself, such as the rediscovery of women artists who break away from its all-male bastion. “There’s a recognition among institutions at the moment that female artists from the old masters period are not properly represented in the galleries, and a lot of institutions are seeking to redress that,” says Sinclair. “It’s a huge area of excitement.”

In 2020, the National Gallery presented a blistering exhibition of work by Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1653) – its first retrospective of any Renaissance or Baroque woman painter. An accomplished storyteller, Gentileschi reimagined the same biblical and mythological scenes as her male peers and predecessors, but did so with an emotional force drawn from the cruelties she herself had faced and overcome; the desperation of Susanna as she’s hunted by the lecherous elders (c.1610), the vengeance of Judith as she beheads Holofernes (c.1613-14), the liberation and sexual rapture of Mary Magdalene (c.1620-5). Directly influenced by Caravaggio, Gentileschi’s own interpretations of biblical stories are arguably more persuasive than his.

,_Artemisia_Gentileschi.jpeg)

For Ng at the Frick, situating classic works in a contemporary art context as per ‘Living Histories’ is just one of many ways to underline their sustained relevance. The curator places greater emphasis on the exchanges being had throughout art history. “Every work of art is having a conversation with whoever is looking at it and that conversation continues to change as the viewer moves through time: every generation, geography and context will create a different perspective,” she says.

Whether viewing classic paintings as a source of inspiration or as a springboard for critique, it’s these fresh and diverse perspectives which will breathe new life into the old masters and keep them relevant for years to come.

-min.jpeg)