Taking Back the Market – How Emerging Artists are Making it in Pandemic Times

Early-career artists are exerting a greater level of control than ever before, creating an art ecosystem rife with collaboration across media and venues. Will it lead to changes in how we value — and buy — art?

When the pandemic put an abrupt end to London’s degree shows last year, the Saatchi Gallery made a shrewd intervention. Partnering with Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery, the Chelsea institution hosted London Grads Now, a selling show presenting work by more than 150 artists from the city’s seven major art schools.

Although it included far fewer works than University of the Arts London’s digital Graduate Showcase — where over 7,000 art, fashion, media, performing arts and communication students featured on a platform built by IBM — London Grads Now retained what is arguably degree shows’ core function: to give early-career artists the opportunity to show their best work to a wider audience beyond their acquaintances — and to potentially attract the interest of gallerists, collectors and buyers.

While Charles Saatchi’s own taste-making meanders around student shows in the early 2000s are as storied as they are controversial, London Grads Now allowed emerging artists to extend greater influence over the show in a number of key ways. Selected graduates had the chance to curate their peers’ artwork (in far more generous spaces than typical shows): from trawling the Graduate Showcase for trends, to installation, setup and lighting.

This level of artist control exemplifies an evolving arts ecology where collaboration and cross-fertilisation are rife, especially for early-career practitioners.

Recently featured in a Financial Times roundup of artists ‘reshaping our way of seeing’, Victoria Cantons curated UCL’s Slade School entries whilst the show’s visuals were created by Central Saint Martins Graphics students, who promoted the exhibition in magazines like Modern Matter. London Grads Now artists have since been selected for shows by the Royal Society of British Artists and Bloomberg New Contemporaries.

This level of artist control exemplifies an evolving arts ecology where collaboration and cross-fertilisation are rife, especially for early-career practitioners. The pandemic has revealed the resilience of existing infrastructure — particularly online viewing rooms and showcases — but this reorganisation predates the recent disruption.

Reforms to arts education; shifts in how emerging artists’ view the market; an increasingly globalised cultural sphere; changing curatorial and commissioning practices; and the mass publicity migration to digital platforms are all rebalancing power in the art world, however monumental that task may appear. Increased transparency, accessibility, diversity and perhaps, a more consistent relationship between merit, acclaim and value are both the causes and effects of these changes. It follows that an artist’s global presence, cultural standing and career trajectory could correspond more clearly to a more open art environment and grassroots scene, reducing the influence of individual collectors and murky valuation practices.

Grassroots activity tends to attract the attention of more established gallerists, proving that reform in art-buying practices is often a knock-on effect from below.

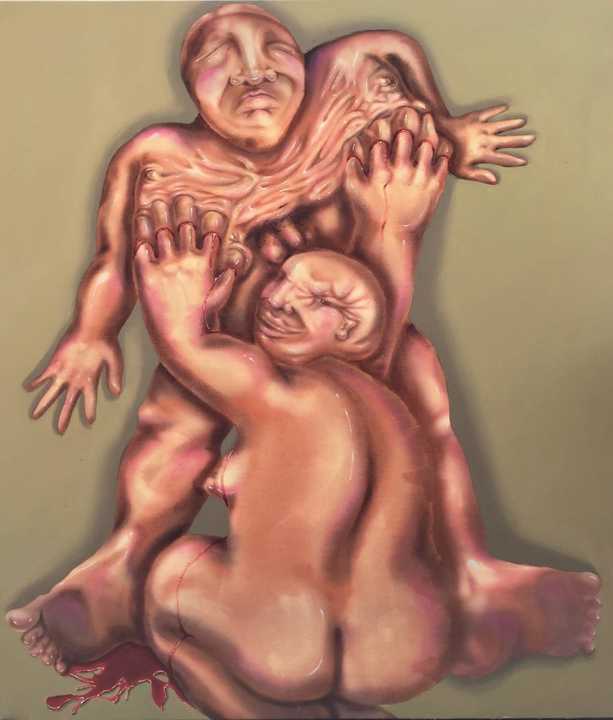

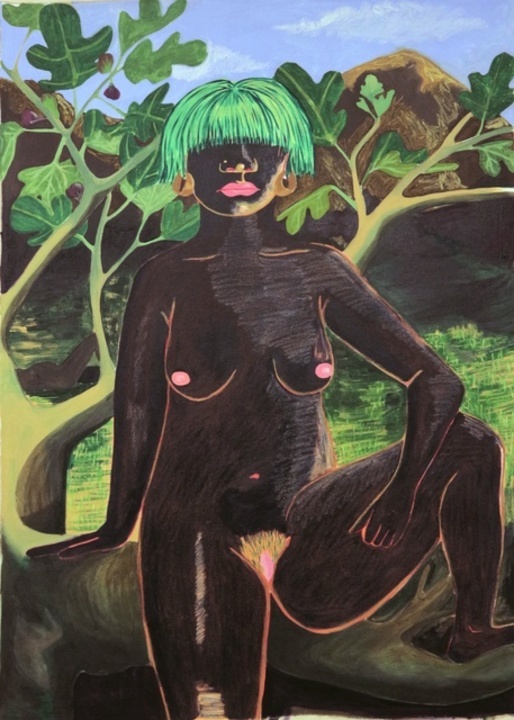

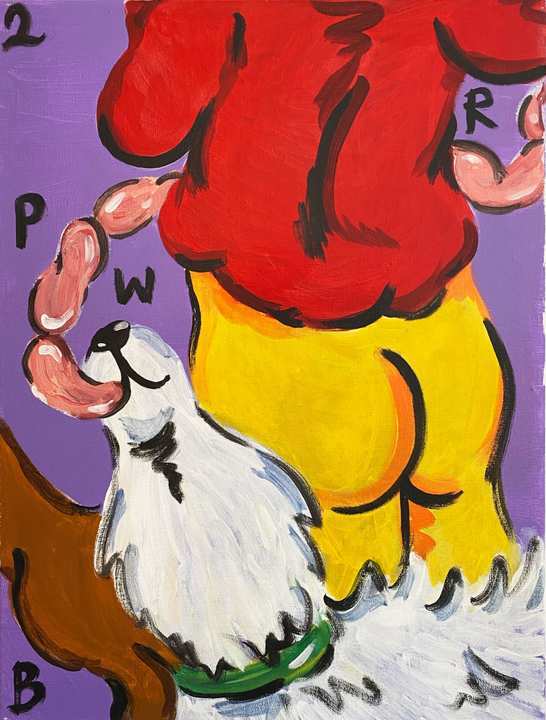

Cantons’ work has also been championed by Guts Gallery, a nomadic gallery aiming to provide fairer compensation to artists and staff by reducing reliance on traditional curatorial models, instead favouring a more intimate style of representation. Founded in response to an art business model that ‘reflects socio-political austerity’ in its lack of support for marginalised artists, Guts combines in-person and virtual (including VR) exhibitions to grow its support base, launching solo shows for the likes of Ruby Dickson, Elsa Rouy and Kemi Onabule.

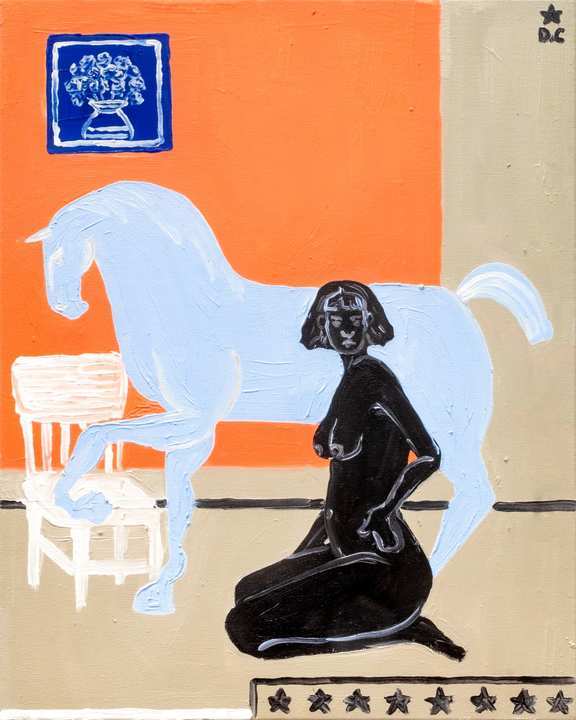

Such grassroots activity tends to attract the attention of more established gallerists, proving that reform in art-buying practices is often a knock-on effect from below. For this year’s London Gallery Weekend, Guts Gallery Introducing was hosted at Sadie Coles HQ, allowing the work of Shadi Al-Atallah, Douglas Cantor, Elsa Rouy, Corbin Shaw, Olivia Sterling and Sophie Vallance to find a more traditional buying audience while retaining a link to their original patron. A self-portrait by Al-Atallah sold for £8,500, along with six of the other ten works on display at the opening.

These partnerships ensure that traditionally underrepresented artists have navigable routes towards sustainable careers, while their presence rebalances an ecosystem which concentrates market — and therefore, cultural — power towards elite networks and interests. Guts are not alone. In fact, they represent just the latest iteration in a growing movement of venues intent on redressing the art world’s inequities, and who employ similar rhetoric towards the old guard. Unit London was founded in 2013, working ‘in an often opaque and unaccommodating art market…to identify, cultivate and expose works of art on a meritocratic basis.’ The gallery has now moved to Mayfair, just a stone’s throw from Cork Street and Savile Row. Currently showing works by the image-heavy painter Ziping Wang, the gallery keenly emphasises its principles of ‘equity, innovation and accessibility’.

Ziping Wang, How Will You See Me Through The Window, 2019 (Oil on canvas, 61x76cm). © Ziping Wang.

For many emerging artists, studying art to BFA or MFA level is the critical springboard for a professional practice. But the gulf between practical, formal training and the commercial rigours of the art world remains significant. Earlier this year, Guts founder Ellie Pennick highlighted graduates’ unpreparedness for the technicalities of the market—particularly the increasing bureaucratisation of funding applications. ‘You need to teach artists how to write an invoice, you need teachers from different backgrounds,’ she said. ‘I think we are on the cusp of something — a definite, necessary shift. There is no time for inequality in the art world, and people are standing up.’

These changes are happening, albeit in educational institutions adopting radically different models to traditional art schools. In New Haven, Connecticut, painter Titus Kaphar runs NXTHVN, a ‘new national arts model’ offering year-long fellowships to emerging artists, curators and high-school students. Based on intergenerational mentorship and local engagement, the programme includes seminars on strategic planning, money management, legal contracts, donor relations, and grant writing.

Again, grassroots action brings attention from blue-chip institutions. From August 2020, Gagosian has endowed NXTHVN’s apprenticeship programme for local high school pupils; launched a professional development programme for NXTHVN fellows; and offered sales support to Pleading Freedom, last year’s exhibition raising funds for racial justice initiatives. A NXTHVN progress report has featured recently in Frieze, and from mid-June, a group exhibition featuring the works of the 2020-1 fellowship artists will show at James Cohan in Manhattan, giving them unique exposure to an otherwise distant New York art scene. Kaphar’s own rapid rise does little to harm their reputation.

I think we are on the cusp of something—a definite, necessary shift. There is no time for inequality in the art world, and people are standing up.- Ellie Pennick, Founder, Guts Gallery

For Xu Yang, a recent Royal College of Art graduate whose work featured in London Grads Now, being an emerging artist is already akin to entrepreneurship, exacerbated by the rise of Instagram and online showcases. “I use every available opportunity to show my works,” she tells me: “exhibitions, talking to people in the pub, charity sales, social media, but without a ‘business plan’ as such.” As with the Graduate Showcase and Unit London’s online viewing space, Platform, it is often emerging and socially-conscious artists and institutions leading this digital upheaval. Their desire to champion works from across the globe—Shandong-born Yang left China to pursue BA Painting at Wimbledon College of Arts—goes hand in hand with the pop-up culture which enables low-cost, high-reach showcases to thrive, and for buyers to be offered genuine choice.

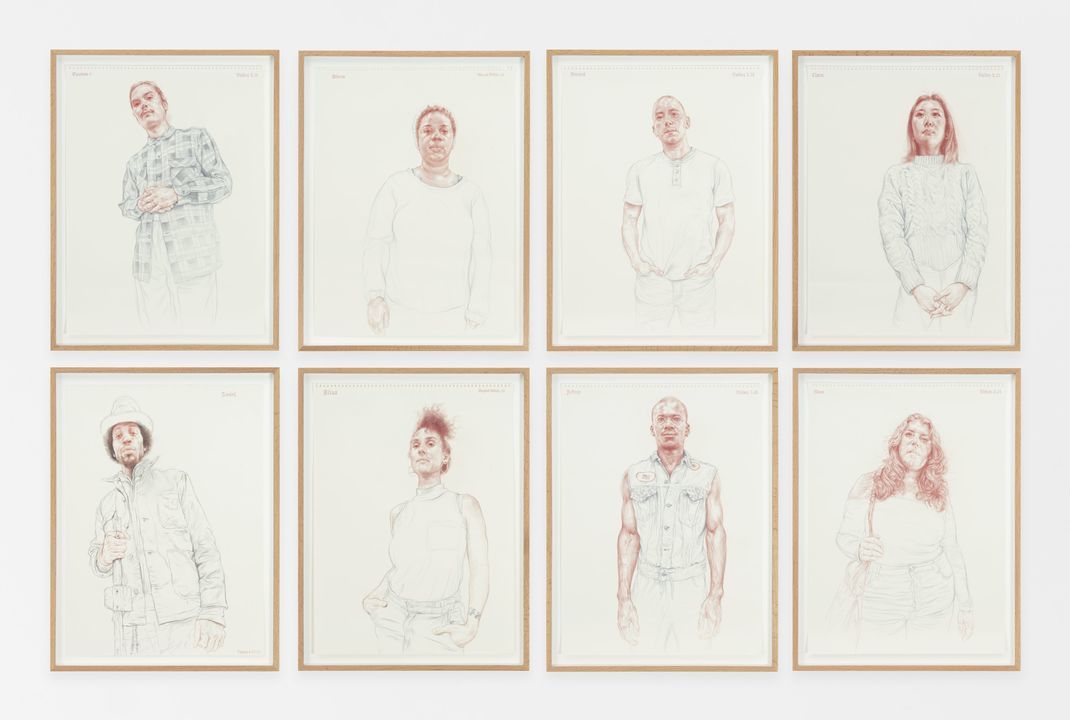

Xu Yang at London Grads Now Show. © Nils Jorgensen.

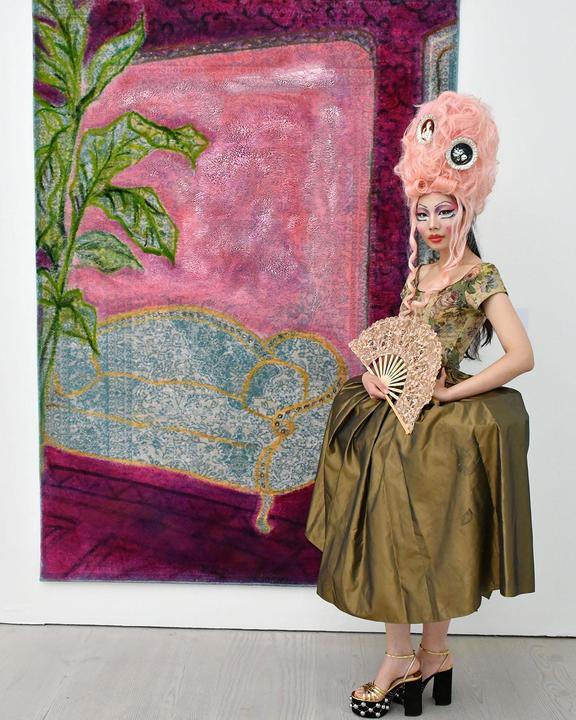

Combining these opportunities with traditional shows illustrates an artist’s range, while also diversifying their audience demographic. Canadian artist Zadie Xa’s first UK solo exhibition is currently mounted at Leeds Art Gallery, while her work also features on New Mystics, a new digital platform collating the works of 12 artists exploring magic, mysticism and artificial intelligence. She will also show new work at Survey II, Jerwood Arts’ annual touring exhibition for prominent emerging artists, which will culminate with a London launch for Frieze week 2021. Such opportunities increase connections and visibility, while also inspiring future projects and collaborations.

Zadie Xa installation at Leeds Art Gallery. © Stuart Whipps.

The surest sign that educational shifts, cultural globalisation, curatorial patterns and digital evolution are rebalancing the art world may when emerging and underrepresented artists spur genuine reform in legacy organisations, rather than thriving mostly in parallel to them. Christie’s digital partnership with the 8th London edition of 1-54 Contemporary Art Fair represents one such example of meaningful crossover (and mutual benefit). Christie’s 1-54 Online allowed visitors to encounter additional works to those on display at the Somerset House show, while selected works from the fair were then on display at Christie’s galleries the following autumn.

The platform ‘enables art lovers from all over the world to see and buy works by some of the best artists from Africa and its diaspora’ said Touria El Glaoui, 1-54’s founding director. It is in everyone’s interests to widen the pool of artists drawing commercial and cultural attention, and appraising deserving emerging artists and making art-buying accessible to all are key goals. Visibility and exposure are not politically, socially or aesthetically neutral forces. While countless doors in the art world remain locked to so many, information and education are the tools for a fairer future.

-min.jpeg)