Witchcraft in the white cube: the resurgence of occult art

Driven by the turbulence of the current moment, a renewed appetite for occultism and esotericism is ascendant in the art world and in the greater digital sphere. As they offer modes of community building that resist dominant forms of culture, these ancient practices are yielding contemporary solutions.

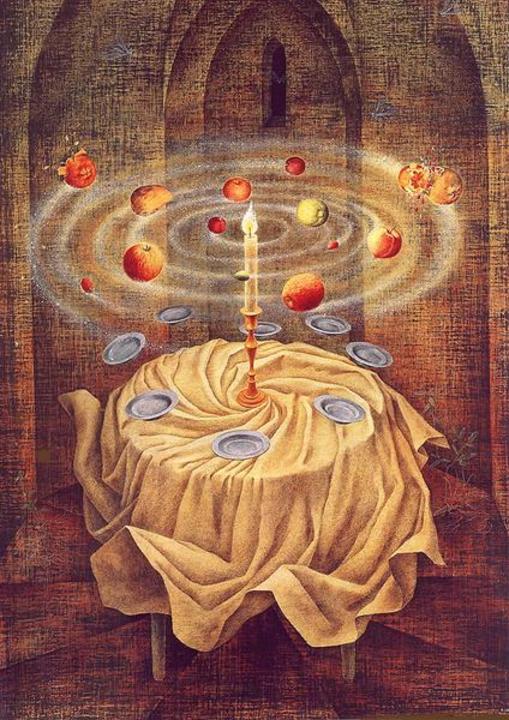

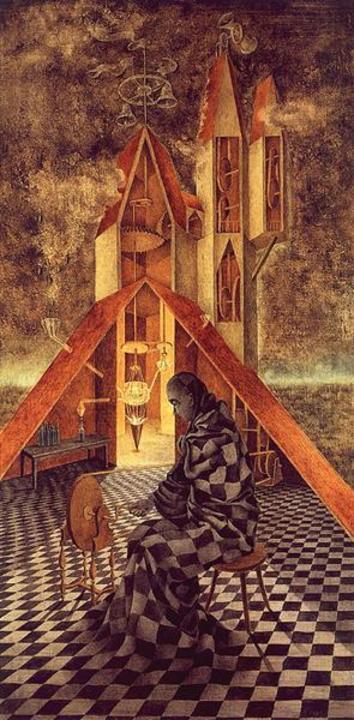

When art historian Susan Aberth began studying Leonora Carrington (1917-2011) in the 1990s, the British-born Mexican surrealist was not considered a “serious” artist. Infused with scenes of sorcery, séances and shape-shifting creatures, Carrington’s inscrutable paintings were largely dismissed as whimsical or childlike. “But I saw immediately the occult content in her work, which is a very serious study,” says Aberth, who has devoted years of her professional life to unravelling it.

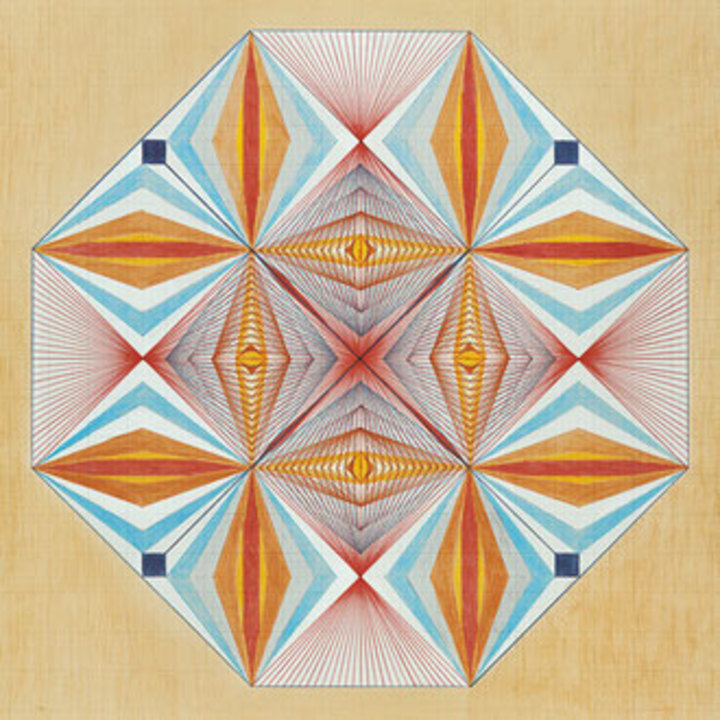

The Pierre and Maria-Gaetana Matisse Collection, 2002. © estate of Leonora Carrington / ARS New York.

During times of disruption, people look to alternative avenues of spiritual sustenance… Where do young people in particular turn? They go back to ancient religions, to things that were hidden and esoteric.

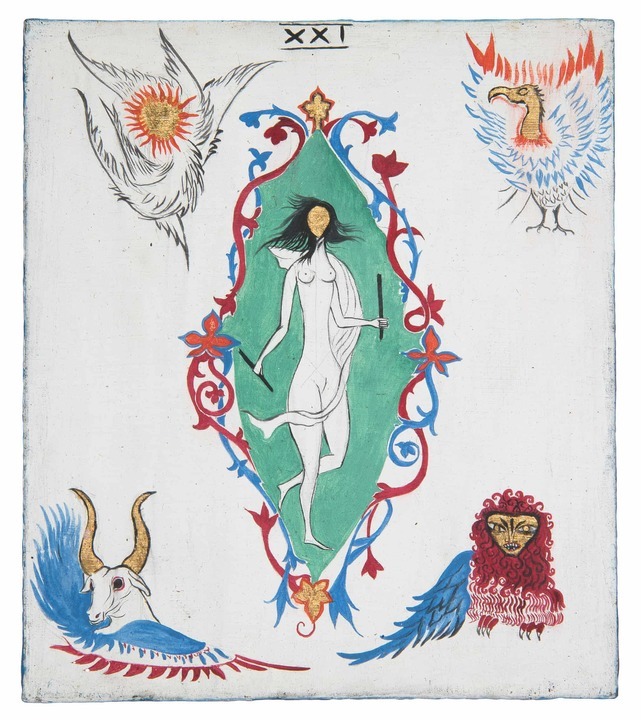

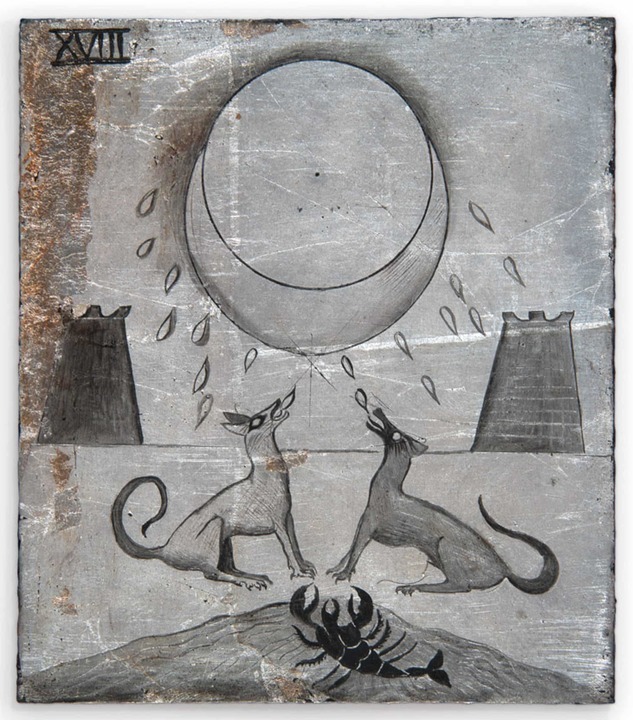

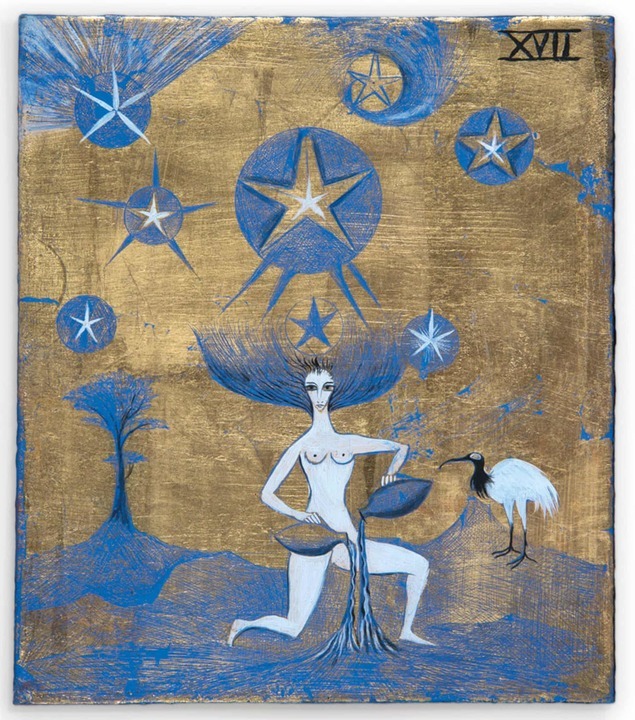

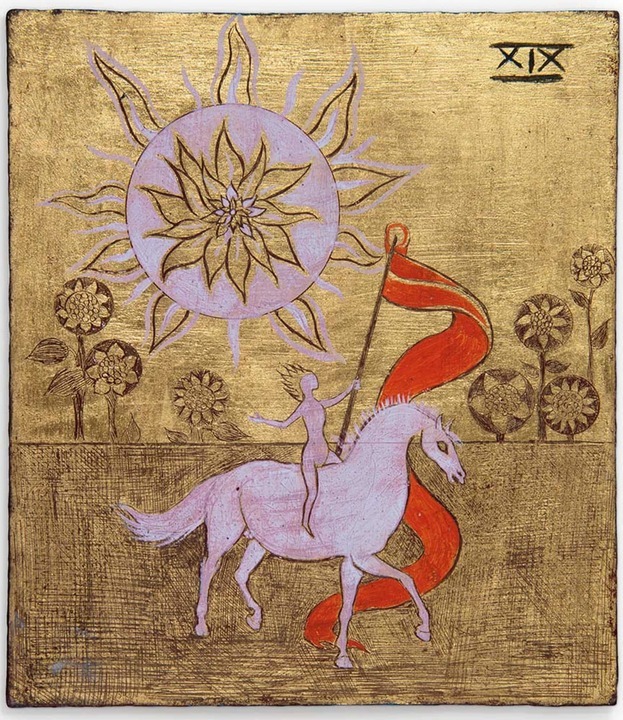

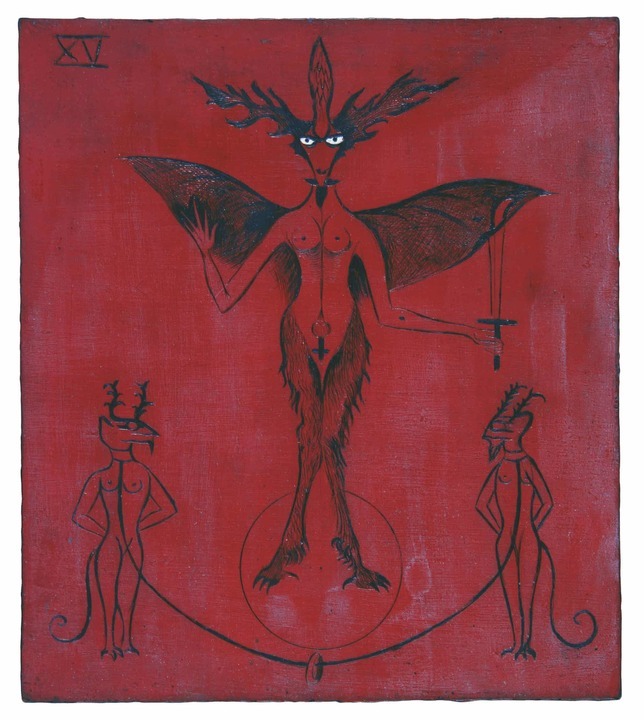

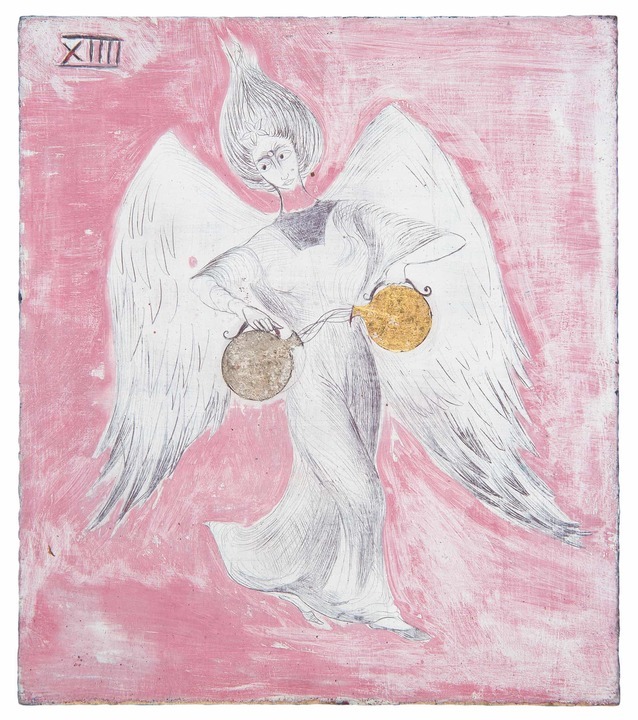

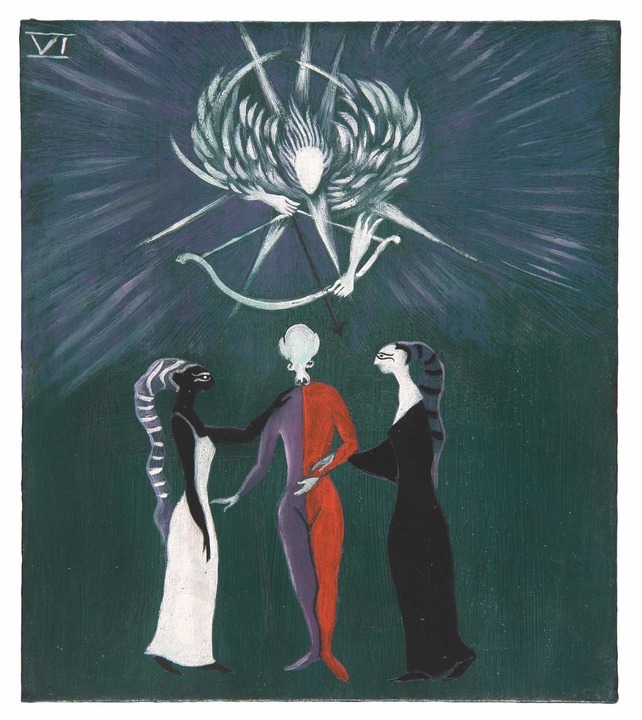

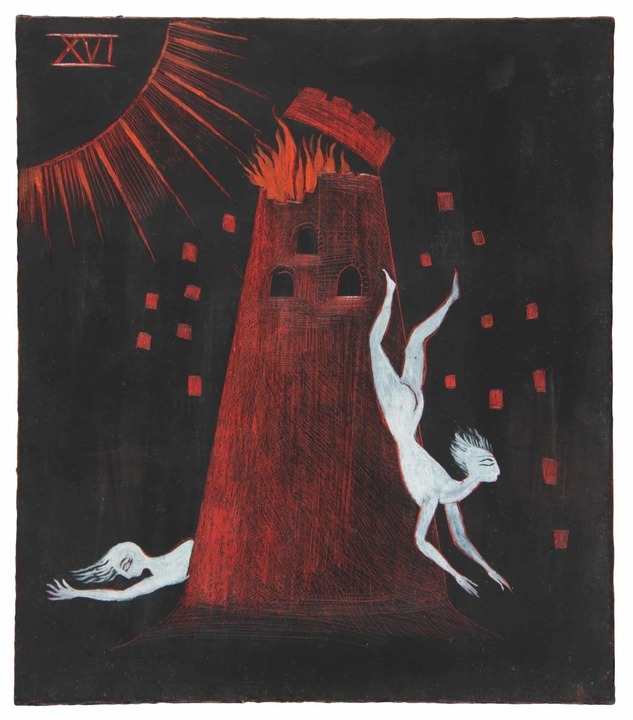

By the time Aberth and curator Tere Arcq discovered Carrington’s private illustrated tarot deck while researching their 2018 exhibition Leonora Carrington: Magical Tales in Mexico City, they knew that “the world was ready to see it”. Even so, Aberth was not expecting the runaway success of their now sold out book, The Tarot of Leonora Carrington, written alongside Carrington’s son, Gabriel Weisz Carrington, and published earlier this year.

“I’m not surprised people were drawn to them, I knew instantly that her images were out-of-this-world fantastic,” Aberth says, referencing Carrington’s spellbinding interpretation of the Major Arcana, rich with colour and sumptuous detail, and roughly dated to 1955. “But the fact that the book was accepted critically by more established journals and newspapers – I was very pleasantly surprised. I guess it was a perfect storm of a resurgence of interest in surrealism, in women surrealists, in Leonora Carrington and in the tarot.”

This wave of interest in Carrington is indicative of a larger tidal shift in the art world towards an appreciation of occultism and esotericism. In 2013, Massimiliano Gioni brought esoteric themes into the curatorial mainstream with his game-changing Venice Biennale, The Encyclopedic Palace, which showcased myriad spiritual cosmologies. Soon after followed a spate of high-profile exhibitions dedicated to rediscovering the work of historic artists like California’s iconic occultist Marjorie Cameron (1922-1995), British spiritual medium Georgiana Houghton (1814-1884), and Swiss healer Emma Kunz (1892-1963). This momentum built up to the Hilma af Klint show at the Guggenheim in New York, which ran from 2018 to 2019: attendance records were broken as crowds flocked to see the Swedish mystic’s spiritually-inspired abstract works.

A renewed appetite for the spiritual exists outside the confines of the white cube, with ‘occulture’ suffusing the digital sphere. The 2010s witnessed the rebirth of astrology among millennials and Gen Z, codified in horoscope apps and memes, while witchy subcultures populate Tumblr and Instagram and TikTok plays host to an ever-expanding #WitchTok community.

Aberth puts this down to the turbulence of the current moment. “We’re living in a time of extreme social change, which is very similar to the 1960s when there was an occult revival as well,” she explains. “During times of disruption, people look to alternative avenues of spiritual sustenance. Many feel let down and alienated by institutionalised religions, young people in particular. So where do they turn? They go back to ancient religions, to things that were hidden and esoteric.”

Looking to occultism, to ancient and goddess cultures, was for Leonora Carrington a reclamation of women’s spiritual power.

Offering modes of community building that resist dominant forms of culture, magic is particularly attractive to marginalised groups. This was a key draw for Carrington, whose esotericism was indivisible from her critique of gender in the mid-twentieth century. According to Aberth, Carrington loved the ritualistic mentality of the Catholic religion she grew up with, but couldn’t stomach the misogyny. Looking to occultism, to ancient and goddess cultures, was for her a reclamation of women’s spiritual power – visible in her tarot deck, in which she casts female figures at the centre of symbolic narratives.

“Feminism and esotericism go hand in hand because they’re about liberating the human spirit,” Aberth says. She sees our contemporary fascination with occultism as part of a long-overdue appreciation of women artists: “I think that women collectors and women curators are driving the market and demanding that institutions purchase works like this.”

Indeed, while Hilma af Klint’s works were hanging in the Guggenheim in 2019, New York’s Museum of Modern Art was expanding its surrealist collection to make it more inclusive. As part of its efforts, MoMA acquired Carrington’s painting ‘And Then We Saw the Daughter of the Minotaur’ (1953), which hangs alongside works by Carrington’s close friend and collaborator Remedios Varo (1908–1963), the Spanish-born Surrealist artist who shared her passion for witchcraft. The market for Varo’s work has also been heating up: at Sotheby’s marathon virtual auction in June 2020, her masterpiece ‘Armonía (Autorretrato Sugerente)’ (1956) smoothly surpassed its estimate of $3 million and left the floor for a record-breaking $6.1 million.

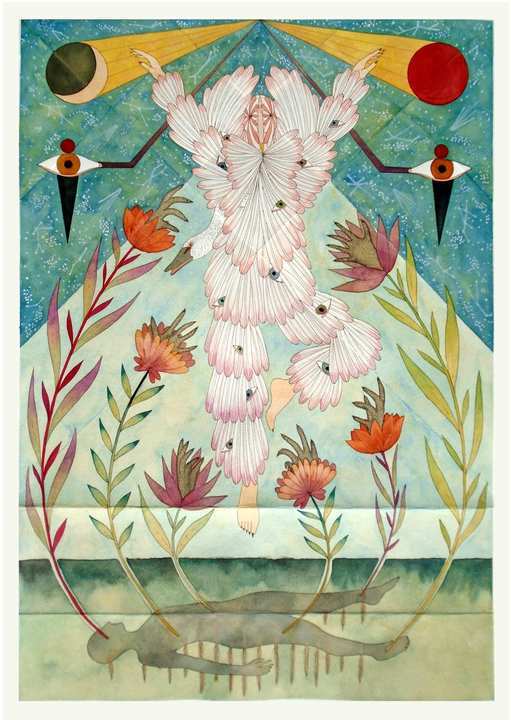

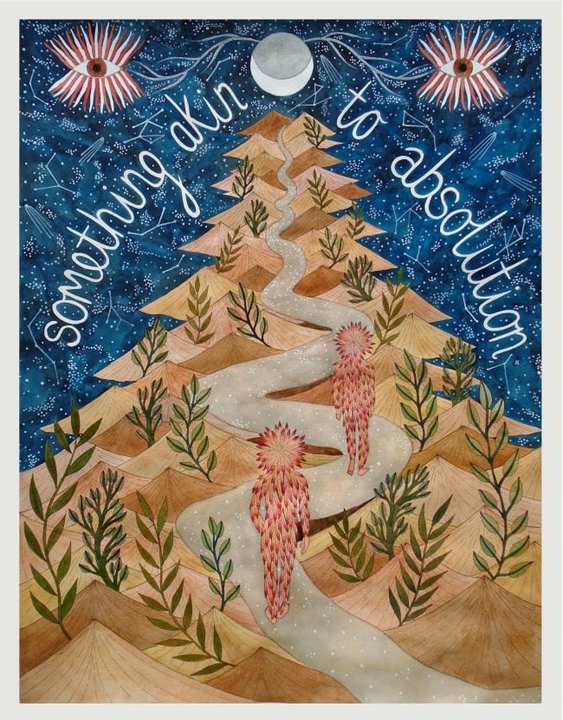

And it’s not just historical artists who are having a moment. At New York University’s 80WSE Gallery in 2016, writer and practitioner Pam Grossman curated Language of the Birds: Occult and Art, an in-depth exploration of more than 60 modern and contemporary artists who engage with magical practice. Among them was Indian painter Rithika Merchant (b. 1986), a mid-career artist with a climbing presence, according to Limna. Merchant’s visionary paintings and collages are inspired by folklore, universal and natural motifs, and comparative mythology – stories that span across cultures.

“I’ve always felt that I’m a little bit from everywhere and nowhere,” says Merchant, who grew up in Mumbai, studied in the US, and now splits her time between Europe and India. “Finding mythical strains of unanimity has made me feel more whole in this world.” In 2017, her intricate symbolic lexicon made its way onto the catwalk after attracting the attention of luxury fashion house Chloé; Merchant’s collaborations with the brand earned her the Vogue India Young Achiever of the Year Award in 2018.

I think it’s because the world is bonkers right now and everything is so out of control – people are literally looking for any kind of divine force to make sense of things, to give them some measure of peace.

Merchant, whose audience is predominantly made up of women in their thirties and forties, has noticed how well mystical art like hers is being received by the market, and believes it goes further than a simple trend. “Whenever I go to openings, the collectors who come and buy seem to want to know the stories behind my paintings,” she remarks. “I can tell they’re not buying it to put it in some warehouse somewhere – people are connecting with the work, it seems to speak to them in some way.”

Like Aberth, Merchant believes that global crises like the pandemic are a driving factor of their appeal: “I think it’s because the world is bonkers right now and everything is so out of control – people are literally looking for any kind of divine force to make sense of things, to give them some measure of peace.” Other contemporary artists leading this esoteric surge on Limna include mid-career American artist Harley Lafarrah Eaves and renowned French artist Hélène Delprat.

If future exhibitions are anything to go by, the art world’s enchantment by the occult appears to be more of a juggernaut than a fleeting trend. The Peggy Guggenheim in Venice is gearing up for Surrealism and Magic: Enchanted Modernity, an extensive survey of the myriad ways in which magic and the occult informed the development of Surrealism. (Due to run from April to September 2022, the exhibition will then move to the Museum Barberini in Potsdam, Germany from October 2022.)

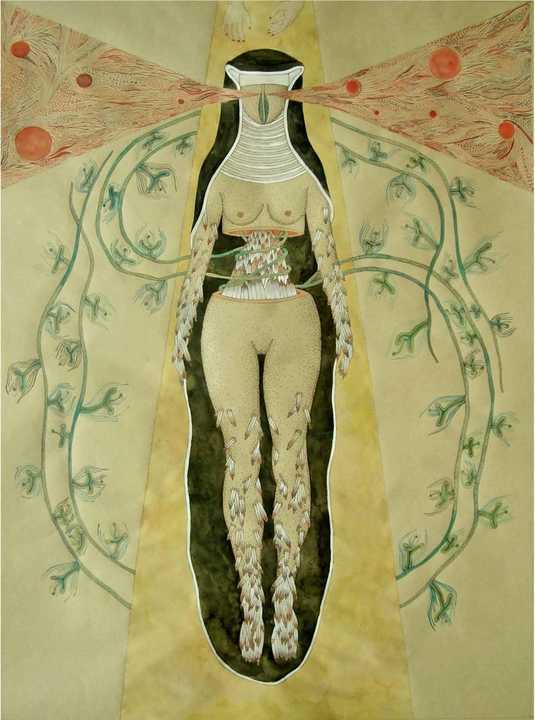

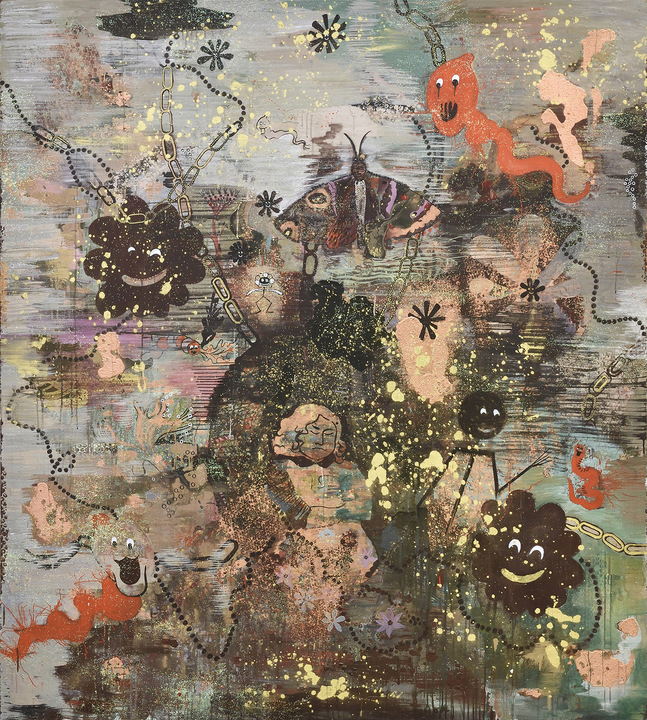

Hélène Delprat, Lost Sleeping Beauty, 2018 © Hélène Delprat.

Making occult art more visible is both a consequence of progressive cultural shifts and a driving force of it. As the art world moves closer to the margins in terms of exploring themes of magic and hidden knowledge – whether rediscovering historical artists or excitedly welcoming new ones – the more inclusive it becomes.

-min.jpeg)