An Enduring Symbol: The continued appeal of the memento mori

Since the 15th century, the memento mori has become one of the most poignant motifs used to explore, express and challenge ideas of mortality. As we move beyond centring human life in all discussions, this genre has similarly evolved to encompass beings greater than our individual selves, and even produce reflections on the afterlives of inanimate things.

Trends come and go, the “must-have pieces” and popular styles of work change constantly, but several genres of work that were prized by art lovers right at the beginning of popular “collecting” have held a continued fascination for artists and their customers. One of the most compelling amongst these is the memento mori or vanitas. The memento mori – as a motif and a genre - grew in prominence between the 15th to the 18th centuries, reaching its zenith in the 17th century.

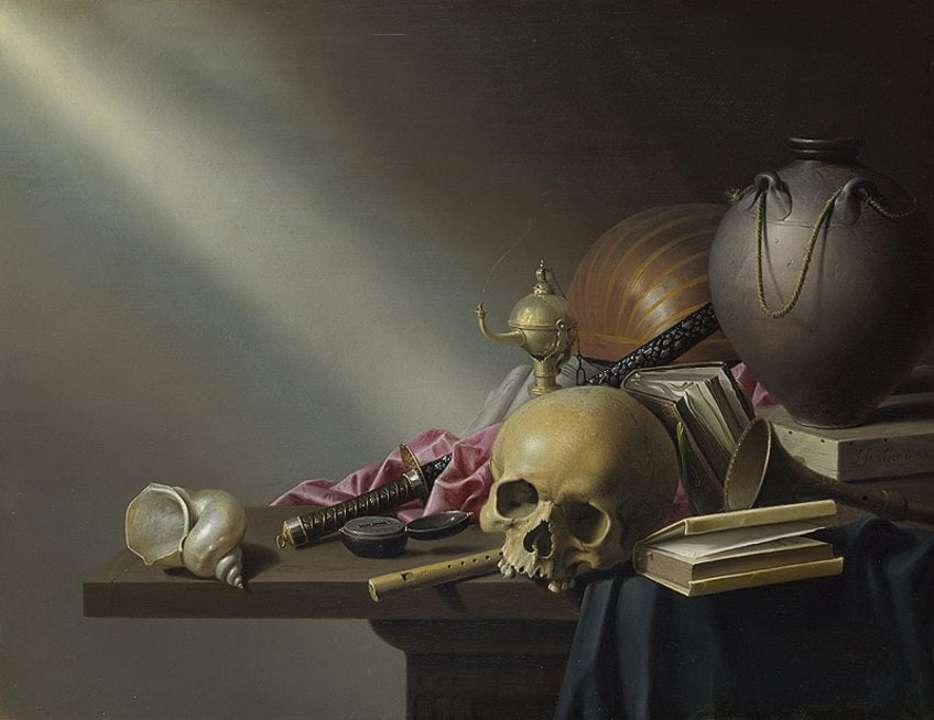

Vanitas Still-Life (c. 1640) by Harmen Steenwijck; Harmen Steenwijck, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Vanitas Still-Life (c. 1640) by Harmen Steenwijck; Harmen Steenwijck, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

During this period an immense shift in European economics, philosophy and policy began, from the monarchic, mercantile and church-based systems of the early modern period to the corporate, colonial and “enlightened” practices and ideals of the coming imperial and industrial ages. This shift in thought away from a highly integrated vision of a natural world under God - in which man was less master of his own fate and more duty-bound to make the most of his predestination - to a worldview in which man was at the head of the great chain of being, with the ability to craft his own destiny.

As God, man and nature became increasingly distinct categories, many artists, patrons, and intellectuals felt more than a few qualms. Aside from wars, rhetoric, and prayer, one of the ways in which they could address these insecurities was through art. Memento mori means literally “remember you will die” and they were commissioned or created as an object of meditation. With advancements in science, technology and economy, wealthy patrons may feel they had become masters of the world, but the reality still remained - from dust he came and to dust he would return.

Memento mori means literally ‘remember you will die’ and they were commissioned or created as an object of meditation. Wealthy patrons may feel they had become masters of the world, but the reality still remained - from dust he came and to dust he would return.

Many visual motifs were used to convey this pointed reminder, such as skulls, dying flowers, spoiling fruit, broken objects, clocks and smoke. In his Vanitas Still Life (1603), Jaques de Gheyn II depicts a bubble, cut flowers, and hoarded wealth – now useless – arranged around a skull.

Over 400 years later, as western society approaches what many intellectual historians are calling the end of the age of “Enlightenment”, having come past post-post-modernism into a world of heightened randomness, it is unsurprising that art which can be seen as the descendant of the memento mori genre, remains one of the ways to explore and express feelings of doubt and alienation surrounding human mortality.

A number of modern and contemporary artists are interested in the value of a reminder that we all die - even if you have a lot of money. Two members of Limna’s top 100, Andy Warhol and Damien Hirst both created modern takes on the memento mori that challenge the viewer’s perception of death.

Installation view, “Andy Warhol: Revelation” at the Brooklyn Museum. Left, two silkscreens titled “Cross” (1981-82); right, “Skull” (1976).Credit…Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY; Jonathan Dorado, via Brooklyn Museum

Installation view, “Andy Warhol: Revelation” at the Brooklyn Museum. Left, two silkscreens titled “Cross” (1981-82); right, “Skull” (1976).Credit…Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY; Jonathan Dorado, via Brooklyn Museum

Warhol’s multiplied Skulls (1976) can be read many ways, but it is a clear example of an artist (and his audience) grappling with individual mortality. For a man obsessed with replication, identity and eternal life through material beauty, the memento mori is both a challenge and a motivating force.

Hirst’s diamond encrusted skull, For the Love of God (2007) is the most notorious work resulting from his repeated engagement with the memento mori. This flashy publicity piece cemented his reputation as blue-chip artist, but he has repeatedly explored skulls and death in his works, indicating an ongoing attempt to reconcile his work, its reception, his desires and his sense of self with the idea of mortality. In the same year, he made I once was what you are, you will be what I am (2007), an editioned etching featuring a much less fantastical skull on an inky backdrop. The title is a direct descendant of 17th century mottoes like ‘he who thinks of death can easily scorn all things’. Perhaps a poignant reminder for an artist whose sales figures are regularly topping the millions.

Jenny Holzer, Living: You should limit the number of times…, 1980-82.© 2022 Jenny Holzer / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Jenny Holzer takes a less visual - but often more visceral - approach to the question of what it means to remember one’s own death. In her Living series (1980-82) she painted onto a sign “You realise you’re shedding parts of the body and leaving mementos everywhere” a subtle take on the concept of “from dust to dust” and a reminder that the best memento mori is our own ageing body. Her Lustmord series is a harrowing account of rape and mass murder that plays brutally with the French notion of orgasm as “la petit mort” or the “little death” - a memento mori in itself if one is inclined to be existential about the nature of eros. A frightening line from the mouth of a Bosnian woman: With you inside me comes the knowledge of my death (1993-4), reminds the artist and viewer not to play idly with such things - that death too often comes in a wave of sadistic cruelty.

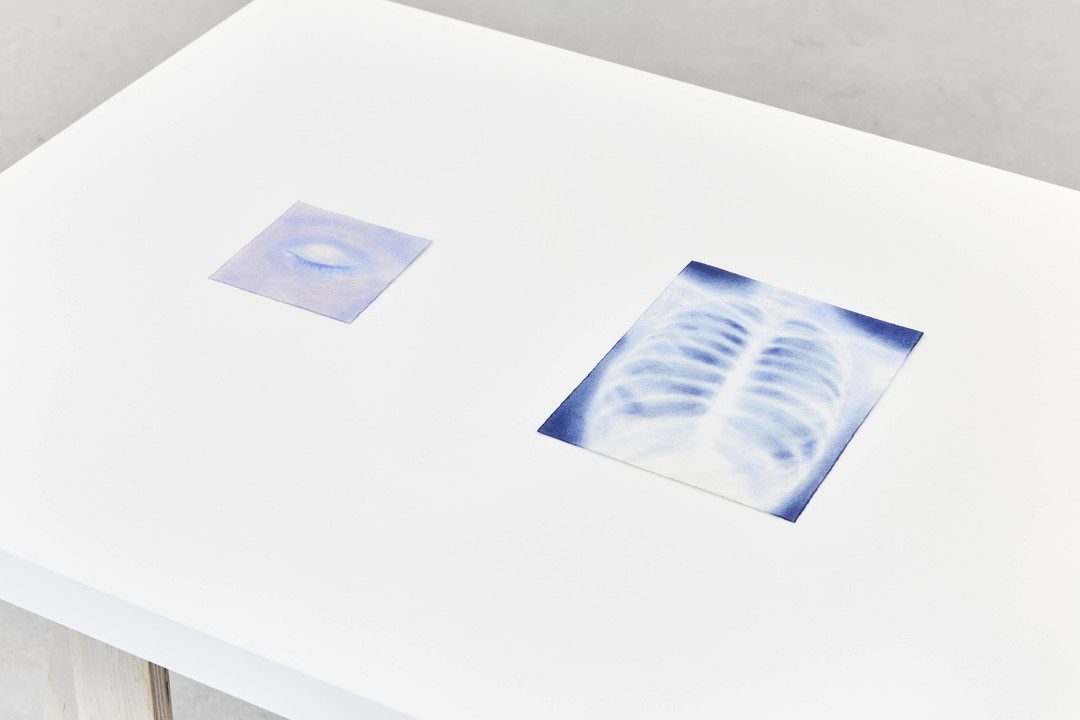

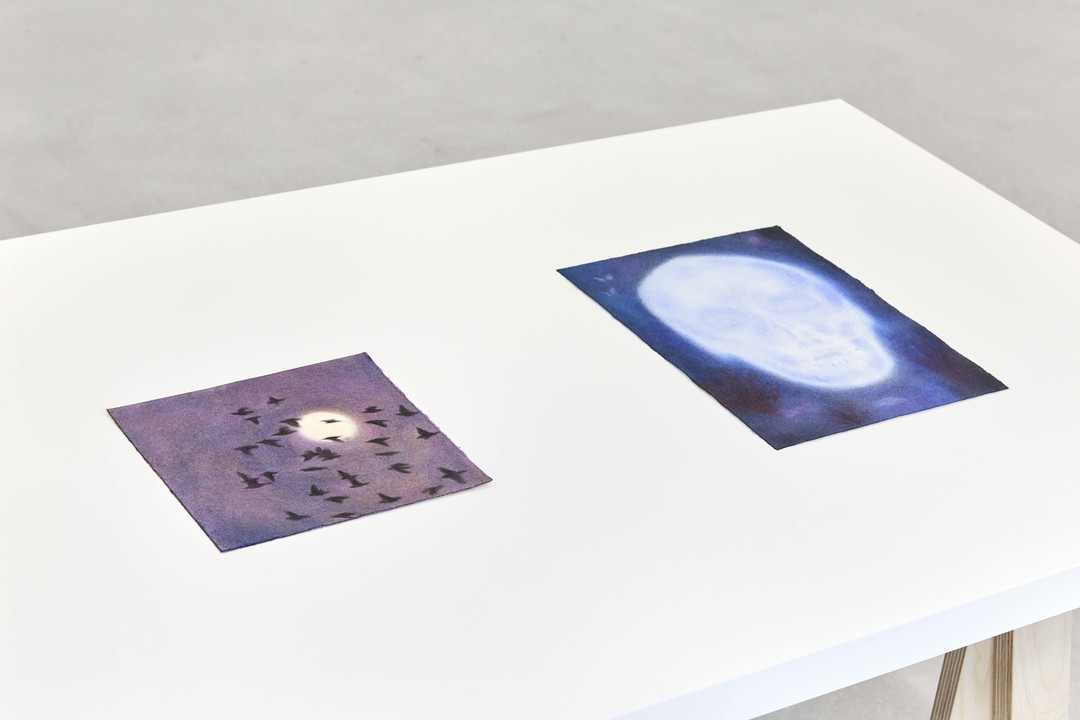

Relatable and humane, Mary Herbert’s work To See Through It (2020) imagines looking down at one’s hands, and seeing through the skin, like an x-ray, to the bones beneath. It’s a contemplative piece in a body of work heavy with symbols of ghosts, urns, cemeteries, blurry memories, secrets and transcendence. Her glowing pastel works appear like dreams, often feature skull-like shadows or skeletons, haunting our unconscious. Her Momentum on Limna has risen rapidly to +30% and she is definitely one to watch.

As we move beyond centring human life and experience in all discussions, we confront the mortality of something greater than our individual self, the Earth and the memento mori genre is extending outwards to the non-human worlds of organic and machine life. Kathleen Ryan’s mouldy fruit, made - in an echo of Hirst’s diamond skull - of semi-precious gemstones, challenge the fantasy of endless freshness and perfection promoted by supermarket produce stands, preservatives, pesticides and “just in time” supply chains. It asks us not just to accept our mortality, but to accept that we live in a world that similarly cycles through life and death. Works like Bad Satsuma (2018) also call back to the vanitas sub-text of the 17th century still-life, where the inclusion of a nibbled cherry, or other symbolic disorder among the shining depiction of luxury foodstuffs was a reminder of the inevitability of decay.

Artists are also starting to consider and produce reflections on the afterlives of inanimate things. In Sun Yuan & Peng Yu’s Can’t Help Myself (2016), a robot flails around in an endless yet futile attempt to clean up a pool of seeping “blood”. A visceral and emotive depiction of a being trapped by bad or indifferent orders/programming, the robot inspired sympathy and horror in many who viewed it. When it eventually became clogged with gunk and its movements became pathetically feeble, it transformed into something more than it was at the start – it became a reminder that machines die too. It asks us to consider: as we make advances in AI through robots and semi-sentient machines, what do we owe these beings?

-min.jpeg)