Ultra Nostalgia and Callan Grecia’s New Ways of Painting

As millennial art buyers come of age, artists tapping into recent nostalgia are set up to resonate with this audience. The familiar references used by Callan Grecia in his works, create a way for people to be drawn into the work through recognition and belonging.

There’s a popular video clip on TikTok of a Nokia 3310 playing the monophonic Hurdy Gurdy ringtone that’s reached 1.9 million views. The Nokia 3310 was released in 2000, the year that gave the Y2K era (1993 - 2003) its name. Over the last few years, to varying degrees of horror, delight and inevitability, the Y2K aesthetic has been enjoying a resurgence across fashion, music, design, film and art. It’s a prime example of the cyclical nature of fashion meeting our insatiable hunger for nostalgia, a yearning that seems to plague millennials in particular.

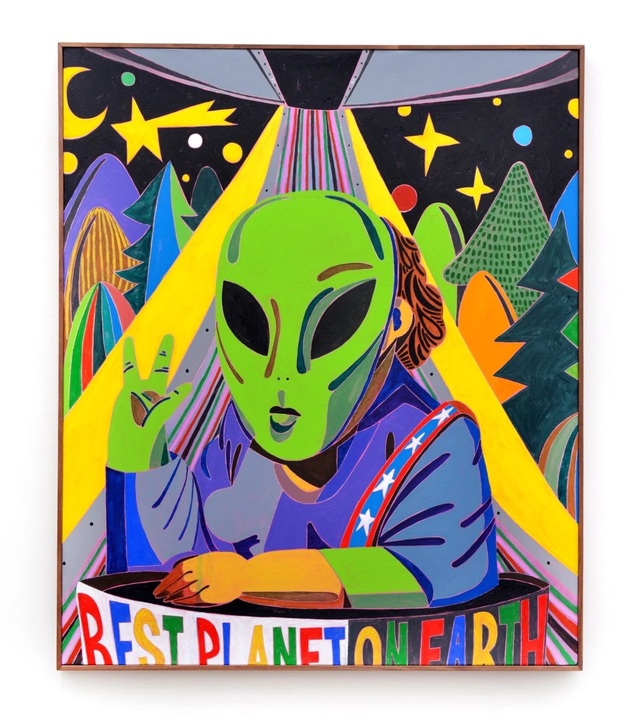

Marble II from Hyporealism, Callan Grecia.

Marble II from Hyporealism, Callan Grecia.

South African artist Callan Grecia was born in Durban in 1991, securing his fate as part of the generation who came of age in the early 2000s. Today he’s to be found in a double garage with a spongy foam floor in the city of George where he’s working on two major solo shows opening later this year; one at Gallery Kiche in Seoul and another at FNB Art Joburg. Growing up, his grandfather would give him office paper from the fax machine on which he drew dinosaurs, cars, clothes and cartoons. He’s still drawing BMWs (a big part of the culture growing up Indian in Durban), soccer balls and streetwear. For his upcoming shows Grecia is going back to his ideal bedroom as a 15 year old and making paintings inspired by what posters would be on the walls. “I was a good general 15 year old,” he says, “wearing my Converse and rap battling. Not super angsty. I’m a little more financially literate, but pretty much the same now. Just a joker.”

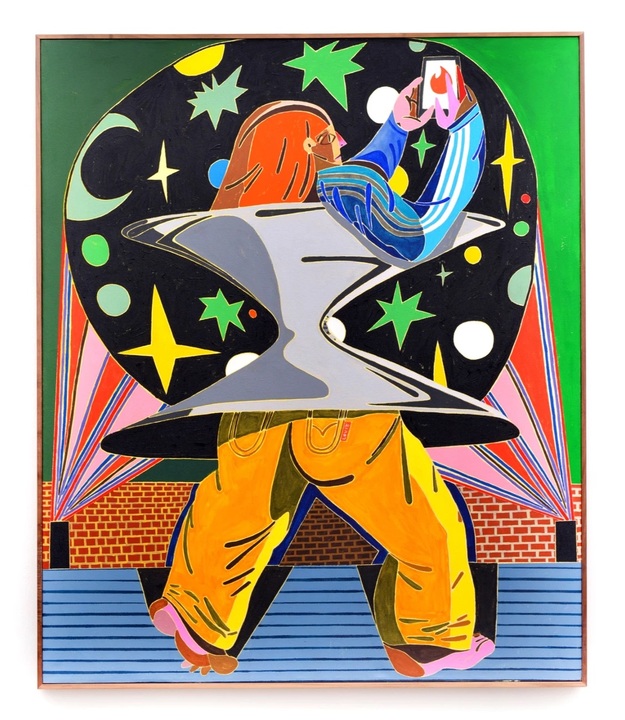

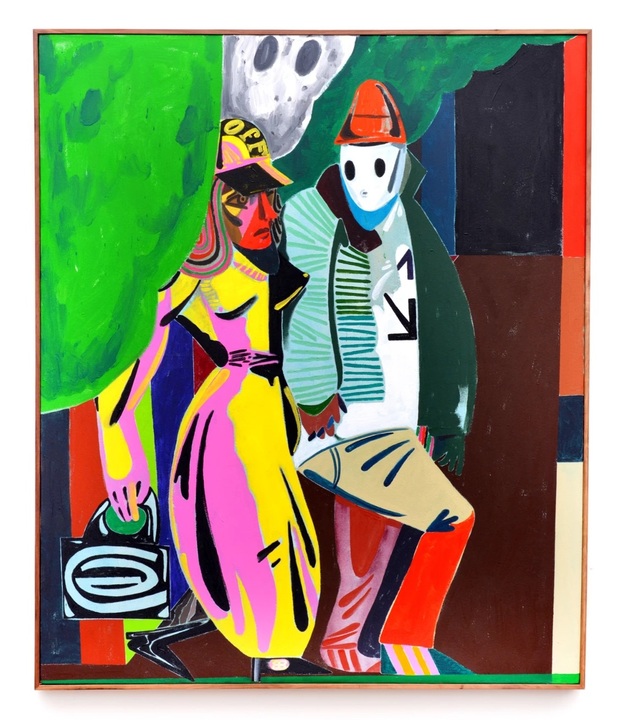

According to Art Basel, millennial art buyers are coming of age and collectors under 40 are showing the biggest year-on-year growth. Artists tapping into recent nostalgia are set up to resonate with this audience. In his 2022 solo show, Hyporealism, at SMAC gallery, Grecia warped timelines by including references to pop culture from the ‘90s through to the current: a green alien mask, adidas Originals Superstar sneakers, Virgil Abloh’s Off-White logo, a cosmic character with a smart phone open to online dating app Tinder and another playing the retro mobile game Snake on the aforementioned Nokia 3310.

According to Art Basel, millennial art buyers are coming of age and collectors under 40 are showing the biggest year-on-year growth. Artists tapping into recent nostalgia are set up to resonate with this audience.

Grecia’s familiar references are used as a device in two ways: the first firmly establishes him as an artist of his generation, making work in the here and now. The second creates a way for people to be drawn into the work through recognition and belonging. Accordingly, his working is showing an increased momentum of 25% according to Limna.

“It’s like writing the simplest song lyrics everyone can get into because it’s so easily accessible,” he explains. “I think that’s in some way what I try to do with the paintings. I have multiple points of access whether that be through fashion, through 2000s or nineties nostalgia, or through a joke; a joke’s an easy in. If they have a point of access, then I’ve done my job.” Once the viewer feels a kinship with the work, they feel comfortable to engage with the deeper meaning.

Nostalgia is something we’ve become well-versed in. It now comes built into the tech we use daily: Facebook memories set to stock music or the ‘For You’ option in iPhone Photos serving compilations of special occasions, or a random Thursday in May. In sync with rapid digital advancements, the rate at which something becomes nostalgic also seems to be on fast-forward. The Matrix being resurrected is one thing, but even a screenshot of an earlier iteration of the Facebook homepage can bring about fond memories. “People want to know ‘What’s the next thing? What’s the next thing?’,” Grecia says, “An iPod is vintage. It’s ultra-nostalgia for things that are not that far away. You can fall into the trap of hyper-nostalgia which I try not to, but I think it’s also fun to lean into.”

Tumblr, the microblogging service launched in 2007, was the first social media platform that Grecia joined as a teen and he’s recently started posting there again. The platform was a place for countless young people to discover and express the identities they were trying on in the passage to becoming who they would be; re-blogging - essentially curating - images from the internet to say: this is who I am, this is what I’m into. The references in Grecia’s work do the same thing. No more so than how his characters are dressed.

“Personally, I’ve got my own little bubble of fashion stuff that I’m interested in,” he says, “I worked at fashion week for two seasons so that exposed me to a lot of different things. I wanted to be part of this, part of that, part of everything.” Some references might be more obscure – a ‘Guilty Parties’ jacket by Japanese brand Wacko Maria – while others like Levi’s jeans will be more recognisable. Everything is what Grecia or his friends are into: “Levi’s 501s is a big thing for me, it’s a very Durban Indian thing.” A striped bucket hat in a painting might be from fashion brand Kapital which brings him a certain IYKYK clout, but it also reminds him of fishing with his grandpa.

Back on Tumblr, Grecia feels more freedom to post whatever he likes than he does on platforms like image-conscious Instagram. He’s finding it a great outlet to post imperfect work-in-progress and smaller pieces that he makes to get his ideas onto paper. “They might even become good paintings,” he says in the caption.

It’s like writing the simplest song lyrics everyone can get into because it's so easily accessible, I think that's in some way what I try to do with the paintings. I have multiple points of access whether that be through fashion, through nostalgia or a joke, which is an easy in. If they have a point of access, then I've done my job.

Grecia received a formal fine arts education at Rhodes University in Makhanda, South Africa where he completed a Master’s in painting. He left with the idea that his art was only ‘real’ if it was big oil paintings though practically he didn’t have the means, or – working from his grandmother’s spare room – the space. His process since has been unlearning aspects of his Western arts education and getting acquainted with acrylics on paper and how it behaves. This essential dismantling of ‘the rules’ has brought newfound freedom in pursuing a unique visual language through which he plays earnestly with proportion, composition and colour.

“If I wanted to draw technically well I could but I’m intentionally drawing shit,” he says candidly. “It brings up so many more interesting compositional things. I think I take myself very seriously as a painter, you have to understand your medium but for me, it frees things up because it’s not based in a reality where I have to get everything perfect, and that’s fine because everything’s not perfect.”

Grecia’s work is becoming more and more his own while leaving signals for others to feel like they’re part of his world. But by recognizing the entry points, we shouldn’t miss the salient point. Take for example, the painting with the 3310. He explains that it’s less about a nostalgic reference harkening back to the past and more about the fact that the person, completely absorbed by the screen, is about to walk slap bang into a brick wall. And therein lies the joke.

-min.jpeg)