Obsession or Therapy? The Art of Repetition.

Insanity is sometimes defined as repeating the same thing and expecting a different result. Yet when is obsession the key to creating transcendental art? Limna investigates.

Art and obsession have long been intertwined.

Anyone who commits themselves to a creative practice, be it visual art, writing or music, likely has an obsessive streak. A person capable of eschewing social contact in favour of perfecting their craft, is often committed to a pathological degree. Often, that obsession coexists healthily with other interests or pursuits. Other times, it cannot.

I recently wrote and released an essay collection entitled Obsessive, Intrusive, Magical Thinking which detailed my own fixations, both good and bad. Due to the way my brain works – I’m autistic – I have more capacity than others for obsession, which can either mean pursuing my own special interests to a beneficial degree, or getting so fixated on a fear that I spiral into compulsive behaviours. My own tendency toward obsession has both benefited and debilitated me, and in writing about it, I started to think about where that line lies for other people. Artists are often obsessive – at what point does that become diagnosable, and when is it just necessary for great art?

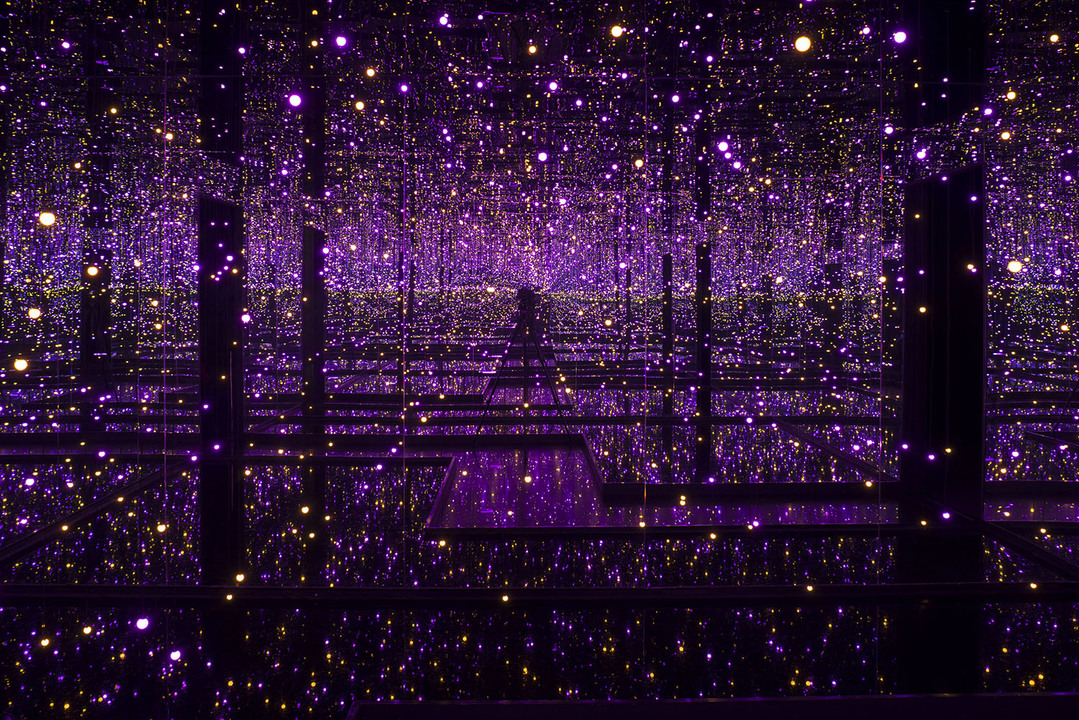

Yayoi Kusama, Infinity Mirrored Room - Filled with the Brilliance of Life 2011/2017 Tate Presented by the artist, Ota Fine Arts and Victoria Miro 2015, accessioned 2019 © YAYOI KUSAMA

Yayoi Kusama, Infinity Mirrored Room - Filled with the Brilliance of Life 2011/2017 Tate Presented by the artist, Ota Fine Arts and Victoria Miro 2015, accessioned 2019 © YAYOI KUSAMA

Yayoi Kusama is the first artist that comes to mind when we think about obsession and the places - creative or unhealthy - it can take us. The artist, born in Japan in 1929, is known for her repetitive, compulsive art, vast fields of hypnotic polka dots and lights. She started drawing her signature pumpkins as a child after seeing them in hallucinations. By the age of 10, she reportedly began to experience vivid hallucinations that she describes as “flashes of light, auras, or dense fields of dots”. Her work, then, be it ‘Infinity Rooms’ or ‘Love is Calling’, becomes an externalisation of that obsession, a way of showing the world what it’s like inside her own head.

Kusama has struggled with her mental health throughout her life, checking into a Japanese psychiatric hospital in 1977. She still lives there through her own volition, continuing to create art and share her own experiences through it. From the way she talks about her own experience, it’s clear that the compulsive way she creates is her way of coping with the noise inside herself.

Art, while a symptom of her own obsessive mental illness, is also therapeutic for Kusama. Speaking to New York Magazine in 2012, she said, “I fight pain, anxiety, and fear every day, and the only method I have found that relieved my illness is to keep creating art. I followed the thread of art and somehow discovered a path that would allow me to live.”

David Zwirner, New York; Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo/Singapore/Shanghai; Victoria Miro, London/Venice

David Zwirner, New York; Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo/Singapore/Shanghai; Victoria Miro, London/Venice

Before moving into the hospital, Kusama emigrated to New York, where she made a name for herself amongst artists like Georgia O’Keeffe, Joseph Cornell and Donald Judd. There, she began her series of Mirror/Infinity rooms, arguably her most stunning and complex installations - rooms lined with mirrored glass and neon-coloured balls. True to their title, the spaces seem to go on forever, representing some small idea of how it feels to live inside Kusama’s mind.

For Kusama, her art and her mental play both with and against one another. In the early 1980s, after she made the brave decision to voluntarily move into a hospital, she stopped exhibiting. Her absence from New York took a toll on her public image, out of sight out of mind, she was forgotten – evident by a sharp decline in her career trajectory on Limna - until a revival in the late 80s and 90s, prompted by retrospectives that brought her back into the international eye.

In 1997, she created an installation series for the Rice Gallery called “Dots Obsession”, a work that confronted a lifelong fixation with not just polka dots, but achieving transcendence through them. She said: “Obliterate your personality with polka dots. Become one with eternity. Become part of your environment. Take off your clothes. Forget yourself. Make love. Self-destruction is the only way to peace.”

Of course, while Kusama has found a way to catharsis through her art, it would be remiss not to touch on the darker side of obsession. Although she said in her autobiography, Infinity Net, that “I, myself, delight in my obsessions”, there is a flip side. “I am deeply terrified by the obsessions crawling over my body, whether they come from within me or from outside,” she goes on to write. “I fluctuate between feelings of reality and unreality.” It’s clear that she straddles a line between absolute control and a loss of it, proliferation as catharsis but without ever being truly in the driver’s seat.

Artists throughout history have often turned to repetition in their works as a way to process their own fixations.

Artists throughout history have often turned to repetition in their works as a way to process their own fixations. Vincent Van Gogh, for example, painted his sunflowers five times, believing they conveyed “gratitude” and happiness, a feeling that eluded him. Andy Warhol, known for his infatuation with pop culture, turned to repeating entire pieces of work over and over again. Working with silkscreens, it was possible for him to recreate images en masse: Marilyn Monroe, Campbell’s soup cans, Coca-Cola bottles, depicted endlessly in grids.

Another notable example of an artist who straddled the line between darkness and productivity was Mark Rothko. Known for his nuanced, repetitive colour field paintings, he created new ways of seeing, allowing the viewer to experience the emotion of colour. By the mid-1950s, experiencing mental health problems in his own life, that darkness began to be expressed through his art. Near-black canvases thick with paint replaced the vivid colour of his early work, and the daunting. Rothko Chapel project in the 1960s feels sombre, almost maudlin.

Installation view of the exhibition “Focus: Ad Reinhardt and Mark Rothko”

Installation view of the exhibition “Focus: Ad Reinhardt and Mark Rothko”

In the 1960s, struggling with ailing health, the artist was diagnosed with a mild aortic aneurysm. Choosing to pursue his life as he enjoyed it, he continued to drink, smoke and eat as he wished. In an attempt to place less strain on his body, his paintings got smaller, and the pieces became tight. After separating from his wife, Rothko moved into his studio, taking his own life aged just 66.

A series produced towards the end of his life stirs controversy in critics and historians over whether they function as “pictorial suicide notes”. The ‘Black on Grays’ as they are known, all featuring a black rectangle above a grey rectangle, if they are not symptoms of depression, they do indicate an obsessive perseverance to carry on doing what he loved despite internal and physical turmoil.

It is perhaps because of this dedication against all odds that their art can achieve transcendence, a feeling validated by everybody who has experienced awe in front of these works – awe at the depth of the work, the perseverance, the eternity. As Kusama wrote: “I felt as if I had begun to self-obliterate, to revolve in the infinity of endless time and the absoluteness of space, and to be reduced to nothingness.”

-min.jpeg)