The Ecological Turn: Art, Landscape and the Environment

Contemporary art’s ecological turn in recent years draws upon traditions that can be traced to the Land Art and Ecofeminism movements of the 1960s. As debates about climate change and environmental damage rage around the world, artists are shedding light on the urgency for meaningful action.

Debates about climate change and environmental damage have been key issues around the world for some time, shaping the development of ecocritical thinking, re-establishing how we think about nature and how we situate ourselves in it. Today, it is more evident than ever that nature and humans are not separate entities, and contemporary artists are placing themselves in the web of life, shedding light on the urgency for change in some instances, promoting the relationship between nature and the urban environment in others, often against a backdrop of community participation and affirmative action.

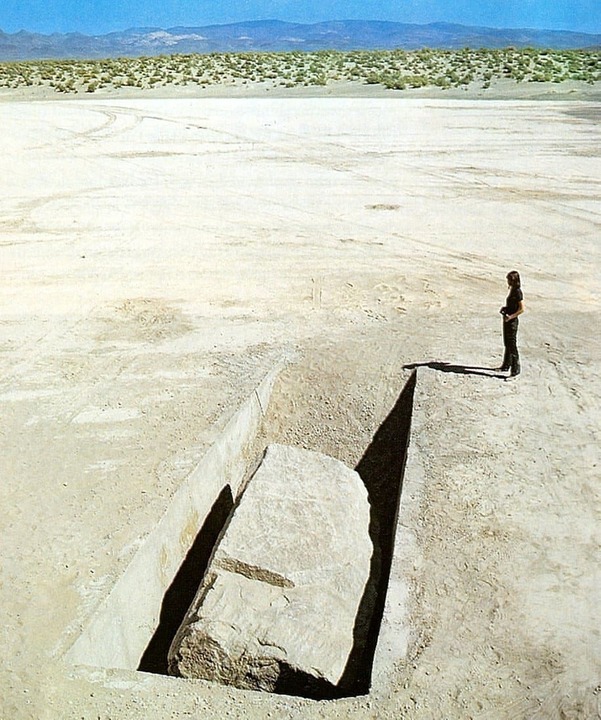

Michael Heizer, Displaced Replaced Mass, 1969.

Michael Heizer, Displaced Replaced Mass, 1969.

Land Art, which rose to prominence in the late ‘60s, is perceived as the first artistic movement to address environmental issues. As artists of the era gradually moved away from the object-centred focus of Pop Art, they started pushing for less conventional definitions of “works of art”. Best known for highly ephemeral works or ambitiously scaled site-specific interventions in remote or hard to reach places, the movement was born out of a direct engagement with nature and landscape.

Famous examples range from Michael Heizer “Displaced, Replaced Mass” (1969), where the artist had three granite boulders relocated into a ditch covered in concrete, to the iconic “Spiral Jetty” (1970) by Robert Smithson, a spiral-shaped dock located in Utah’s Great Salt Lake. Although the exploration of environment, time and space, as well as ideas of non-human agencies shaping the work as much as the artist, the movement was criticised for its imposing and manipulative approach towards nature, often resulting in invasive interventions lacking ecological sensitivity. For example,”Spiral Jetty” required the relocation of more than 60,000 tons of soil, basalt and salt crystals by excavators and lorries over the course of a year.

Spiral Jetty, Robert Smithson, 1970.

The British artist Richard Long took a different approach. His work was less concerned with leaving a visible mark on the landscape than reaching areas where nature had not yet been subjugated by man, stimulating ethical and ecological debates. Interestingly, Long is the only artist of this group which still has an upward Momentum according to Limna.

Lesser known at the time, but increasing in relevance today, is the Ecofeminist movement which also developed during a climate of charged political activism in the late ‘60s across Europe and the United States. Through the work of theorists and artists, the movement exposed a critical link between environmental degradation, the exploitation of nature and the oppression of women in a patriarchal society governed by a colonial mindset. Amongst its proponents, Agnes Denes and Cecilia Vicuña, are both participating in the 59th Venice Biennale this year, and have respectively a +1% and + 5% Momentum.

Ecofeminism was once dismissed as a lunatic and marginal movement, but new ecology-centred languages of art are re-asserting its aesthetics of care and active participation.

In 1973, Ana Mendieta started developing her “Siluetas” series for which she carved and shaped her figures in earth, ice and water. These works showed an approach to nature closer to the archetype of the feminine, where body, nature and the spiritual are connected and the boundaries between them become blurred. Meanwhile, the public artwork “Wheatfield – A Confrontation” (1982) by Agnes Denes, a field of golden wheat planted on two acres of rubble-strewn landfill near Wall Street and the World Trade Center in lower Manhattan, became one of Land Art’s great transgressive masterpieces. Going beyond the movement itself, it paved the way to a series of works calling attention to deteriorating human values and misplaced priorities, as well as encouraging audience engagement with the art piece, as the wheat was left there for the community to deal with.

“Wheatfield – A Confrontation”, Agnes Denes, 1982. Photo by John McGrail, Courtesy Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects.

“Wheatfield – A Confrontation”, Agnes Denes, 1982. Photo by John McGrail, Courtesy Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects.

Prompted by the climate crisis, similar ideas are underpinning contemporary art’s ecological turn in recent years, bringing it from academic discourse or activist movements into everyday life. In 2014 Olafur Eliasson used displacement and relocation techniques typical of the Land Art movement, to harvest twelve large blocks of ice from the Greenland ice sheet and display them in public places, providing a direct and tangible experience of the reality of melting arctic ice. The project, titled “Ice Watch”, has appeared in Copenhagen, London and Paris, during UN Climate Conferences or Assessment Reports on Climate Change.

,%202021.%20Courtesy%20of%20Amakaba.%202.png)

The opera performance “Sun & Sea” (2017) by Lithuanian artists Vaiva Grainytė, Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė and Lina Lapelytė also received popular acknowledgement when it won the Golden Lion award at the 58th Venice Biennale in 2019. Presenting a group of vacationers on the beach, the opera is staged in leisurely harmony while performers sing about their mundane existence, worries and boredom. When listened to attentively, the libretto’s contents reveal dark remarks on Earth’s deterioration and our human indifference to it.

More recently artist Tabita Rezaire founded “AMAKABA” (2021): a self-sustained agroecological cacao farm, yoga centre and home for collective healing located in the Guyanese Amazonian Forest, where art, science and spirituality convene to preserve the forest. The French-born Guyanese/Danish artist is known for navigating digital, corporeal and ancestral memory as sites of struggle, as well as working at the intersection of visual and therapeutic arts and communication sciences. Moving away from western traditions, the artist presents a technology-based holistic approach, and is one to keep an eye on with a rising +14% Momentum on Limna.

Art Now, Cooking Sections, Salmon: A Red Herring, Tate Britain. Cooking Sections; Photo credit Lucy Dawkins.

Art Now, Cooking Sections, Salmon: A Red Herring, Tate Britain. Cooking Sections; Photo credit Lucy Dawkins.

Finally, London-based duo Cooking Sections – nominated for the Turner Prize in 2021 - has collaborated with the head chefs of both the Tate Britain and Serpentine restaurants to create a minimum-waste menu, featuring filter-feeders and regenerative coastal ingredients that support marine ecology around the UK.

The intervention is part of the long-term initiative “CLIMAVORE”, initiated by the duo in 2015 which includes a variety of self-initiated or commissioned site-responsive projects. It began with the installation of an oyster table on the Isle of Skye to pivot from an economy dependent on salmon farming, which causes pollution, to one based on filter feeders and seaweeds, which are crucial in maintaining robust and healthy ecosystems. Collaborating with farmers, restaurants and local stakeholders, Cooking Sections have set up an apprenticeship programme and are currently working towards the establishment of an intertidal polyculture farm to cultivate food, ecology and habitats.

“The brain itself resembles an eroded rock from which ideas and ideals leak”, wrote Robert Smithson in 1968. His contributions were significant, but in the end, he saw nature as something that could be dominated and colonised. In contrast, Ecofeminism was once dismissed as a lunatic and marginal movement, but new ecology-centred languages of art are re-asserting its aesthetics of care and active participation.

CLIMAVORE oyster table, Isle of Skye. Courtesy of Cooking Sections.

CLIMAVORE oyster table, Isle of Skye. Courtesy of Cooking Sections.

###

-min.jpeg)