What is Art Data?

The primary art market is full of opportunities for discovering incredible new artists, and art data makes it a lot more transparent.

If you were an artist trying to make it in 19th century Paris, you’d likely be vying to have your work included in that year’s Salon. Originally meant as a competition to determine the best paintings, the Salons quickly became known as a place where artists could make their name, as well as cozy up with collectors to sell their works. Pricing was established through a complex web of social and cultural connections: if a new artist’s work won a prize, or was exhibited next to other, better-known works, its value could increase by several thousand francs overnight.

Today’s art market still largely resembles the Salons of 19th century Paris. The primary market — galleries and individual dealers who sell work directly from the artist — are still the driving force behind an artist’s career. While some collectors prefer the transparency of the auction market, the best investments tend to come from purchases made on the primary market. These works are often new from the artist’s studio or have never been sold before. Decades before Basquiat’s paintings sold for more than $100 million at auction, gallerist Larry Gagosian was buying the works from the artist himself for just $3,000 and reselling them to clients.

While auction data is readily available, you’ll almost never see a price tag on a work at a gallery. Christies and Sotheby’s each offer estimates in advance of an auction and publicly list the hammer price of the work. But getting a price list from a gallery in Mayfair or Chelsea can be difficult if you don’t already have a relationship with the gallerist.

On its surface, the whole system seems incredibly arbitrary — until you look at the data underpinning the prices.

If you were buying a home in the US, chances are you’d check Zillow or another real estate site to get a sense of what that property is worth. Unlike an estimator, Zillow doesn’t inspect your home or know the precise value of the property you want to purchase. Instead, it offers data about similar sales in the neighborhood, as well as those homes’ features. While it’s far from a firm estimate, the tool can help you decide whether or not a home’s list price is fair.

With a house, it’s fairly easy to quantify its assets: square footage, age, and even renovations are reflected in publicly available sources. When it comes to art, there are certain factors that almost always affect the price of a work. Larger artworks tend to be worth more than smaller ones, paintings more than photographs, and originals more than lithographs or screenprints.

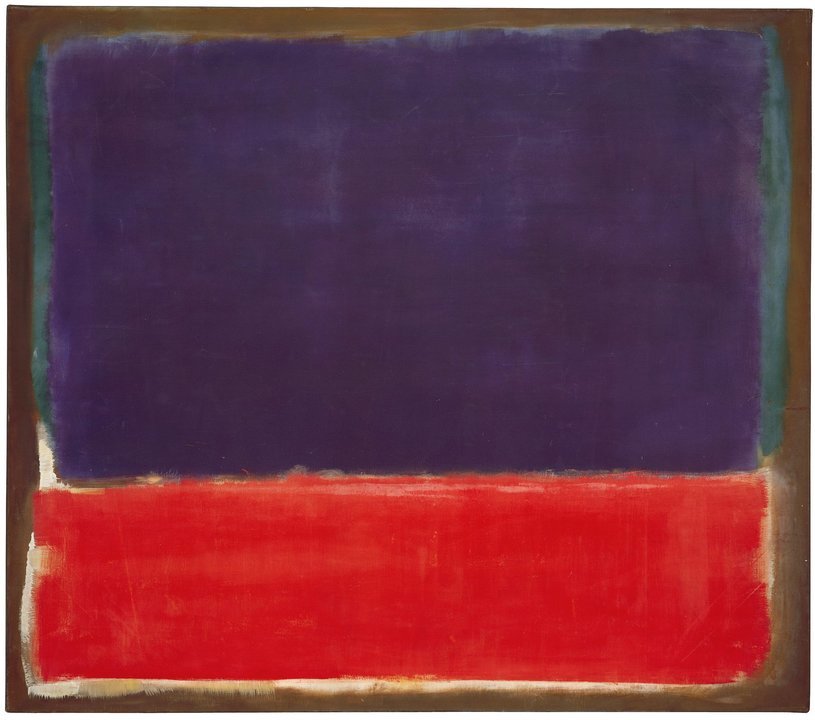

But a piece of art is a creative work that contains a host of personal and emotional factors that are difficult to quantify. How do you put a price tag on the intensity of interacting with a Richard Serra sculpture or the visceral emotion of a Rothko?

The price of an artwork is also affected by a host of social and cultural factors that can be difficult to quantify.

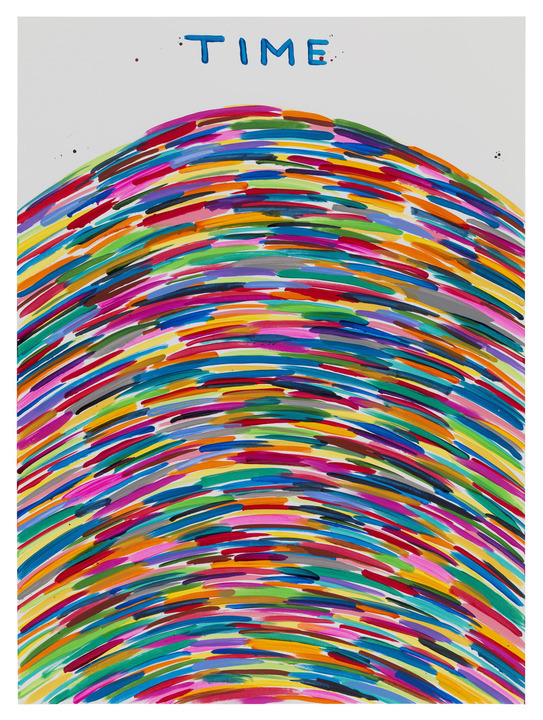

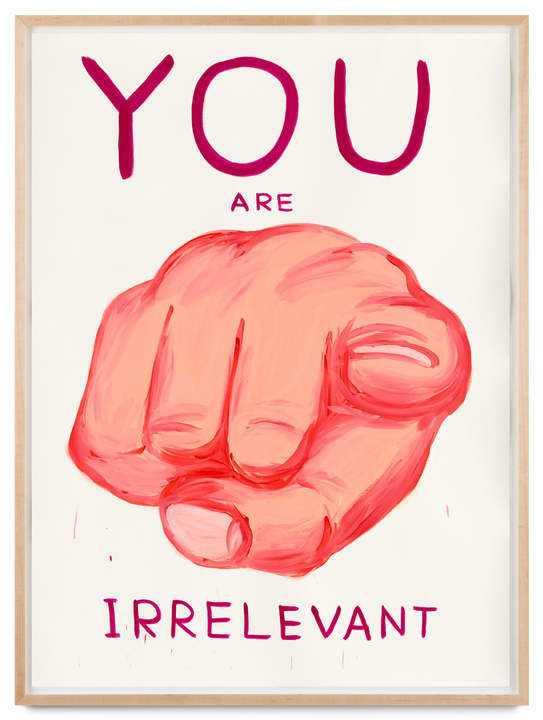

David Shrigley, a British artist known for his cartoon drawings on paper, which are usually peppered with adolescent humor and references to memes and other pop culture symbols. Bel Fullana, a young Spanish artist, makes similar, pop-inspired works, but there is a significant difference in the price. Yet, their subject matter and technique are similar and neither has the celebrity status of someone like Andy Warhol. If anything, you’d think that Fullana’s works, which are all originals, should be worth more. But they aren’t — Fullana’s paintings go for between £360 ($500) and £750 ($1,000), while screen prints of Shrigley’s works range from £2000 ($3,000) to £7000 ($10,000) on the primary market.

-2006.jpeg)

An art advisor could tell you that Shrigley has far more cultural cache than Fullana. Shrigley is represented in New York by Anton Kern, a gallery that also represents big names like Nicole Eisenman and Nobuyoshi Araki. His works have also appeared in group shows at major institutions like the MoMA alongside Louise Bourgeois and Jim Dine. The Hammer Museum also hosted a solo show of Shrigley’s works, a major step in an artist’s career. In all, Shrigley has had almost 500 exhibitions, most of which have been in the US and UK, both highly lucrative markets.

Fullana, on the other hand, is represented by Freight + Volume, a smaller gallery on the Lower East Side of New York. In total, she’s had about 20 shows, most of which have been at smaller galleries and museums in Spain and Portugal. That isn’t to say that Fullana is not as good of an artist as Shrigley. Rather, it suggests that the price of Shrigley’s work isn’t set as capriciously as it may appear.

Instead, dealers use their knowledge of the artist, his career, and his connections to other artists to make a rational decision about the value of Shrigley’s work. The validity of those pricing decisions can be confirmed using publicly-available data from the auction market, which shows a correlation between Shrigley’s exhibitions and the total sales of his work at auction.

The same holds true for the majority of artists. Limna tracked more than 100,000 artists, both before and after their works appeared on the secondary market. They mapped these artists’ performance according to their career trends, an aggregate measure of the prestige of their exhibitions, who they have exhibited alongside, and who the curators were. They found that a positive career trend almost always led to additional sales at auction. Approximately 70% of artists with a high positive career trend (all data measurements tracking sharply upward) made it to auction, compared to just 15% of those with a regular career trajectory.

Because of this informal system, the art market is also highly susceptible to hype. This happens so frequently that there’s a term for these fast-fading wonders: art world darlings. These artists rise quickly amidst intense buzz, only to disappear shortly thereafter. In that time, the value of their works jumps significantly (and, after they fade, fall accordingly). Oscar Murillo, one of the best-known art world darlings, has continued to exhibit frequently and shatter auction records. For others, the hype can fade in a matter of months, damaging their careers in the long term. But by tracking artists from when they first emerge, art data can help collectors discover new artists with strong career trajectories.

Oscar Murillo, 2020. © Photo by Julián Valderrama

Oscar Murillo, 2020. © Photo by Julián Valderrama

The official Salons in Paris started their slow decline after disenchanted artists and collectors began to form rival venues. Many were frustrated with the conservative taste of the Academy, which doled out awards at the exhibition. The Academy took a narrow view on art, rejecting avant-garde practices, instead favoring realistically-rendered mythological scenes and traditional portraiture. These new venues appealed to a wider range of aesthetic sensibilities, allowing individual artists to show their work, regardless of whether it fit into the Academy style. More than ever, individual taste reigned supreme.

While the contemporary art world still maintains some of the structures of the original Salons, the diversity of the works for sale resembles these latter events. Gallerists and social connections still form the backbone of the art world, but the average collector now has far more room to explore and develop their taste. When it’s done correctly, art data can guide you through this process, helping you find new artists or establish a basepoint for a work’s value. The rest is up to you.

-min.jpeg)