What is TASTE?

To this day, taste remains something elusive, unquantifiable: it’s like trying to grab a handful of water. What does it mean to have “good” taste in art? Limna explores a few avenues.

“All life is a dispute over taste and tasting,” wrote Nietzsche in Thus Spoke Zarathustra: A Book for All and None. Not much has been sorted out since that sentence was published in 1883. Taste remains something elusive, unquantifiable: it’s like trying to grab a handful of water.

Either you have good taste, or you don’t, is the oft repeated, rather meaningless phrase. But when it comes to art - which has codified and institutionalised certain types of work as worthier of our attention than others - what does it mean to have “good” taste? Limna explores a few avenues.

First of all - what is “bad” art?

Since opening its doors in 1993, the tiny, underground Museum of Bad Art (MOBA) in Boston, Massachusetts has had a peculiar approach to the concept of curation. Their aim is to “celebrate the labour of artists whose work would be displayed and appreciated in no other forum.” Anatomically incorrect, overly-colourful and heavy-handed allegories abound.

In one painting, Jackie Kennedy stares, mouth open in mid-sentence, at what is either George Washington or a very badly constructed Willem Dafoe in cosplay. The proportions are wildly off, the pairing is Hot Tub Time-Machine absurd, and Jackie’s teeth look like they have been modelled off canned corn. It’s art so bad, it’s good.

Anna Choutova artist, curator, founder & director of Bad Art

Anna Choutova artist, curator, founder & director of Bad Art

Curator Anna Choutova explained her definition of bad art during her 2016 “Bad Art” show. “Bad Art is unchallenging, safe and stale,” she said. “Art that has nothing new to offer, nothing interesting to bring to the table. Background noise if you will, elevator music. I think that the worst art is art that has the least capacity to be disliked by the viewer.”

Provocation is one quality, especially in contemporary art, but this limited, classist view ignores the role of art in cultures around the world: to tell stories, to soothe, to educate, to continue traditions. Besides, some of the “bad” art at the MOBA is extremely thought-provoking. But Choutova’s comment raises an important point: aren’t variety and critical thinking necessary in order to grow one’s taste and learn to appreciate nuance in art?

Are digital algorithms the new didactic curator?

Social media platforms - Instagram in particular - have become fascinating spaces to dig deeper into the concept of taste. Unlike galleries, art fairs, and museums that create a top-down approach to art, selecting what is and isn’t “good” for us, social media offers the illusion of agency. Your algorithm is guiding you to “discover” our own taste based on previous posts you’ve liked or archived, creating a circular loop of satisfying content.

Is this really us curating our own taste? Or are we being siloed into what the internet thinks we like?

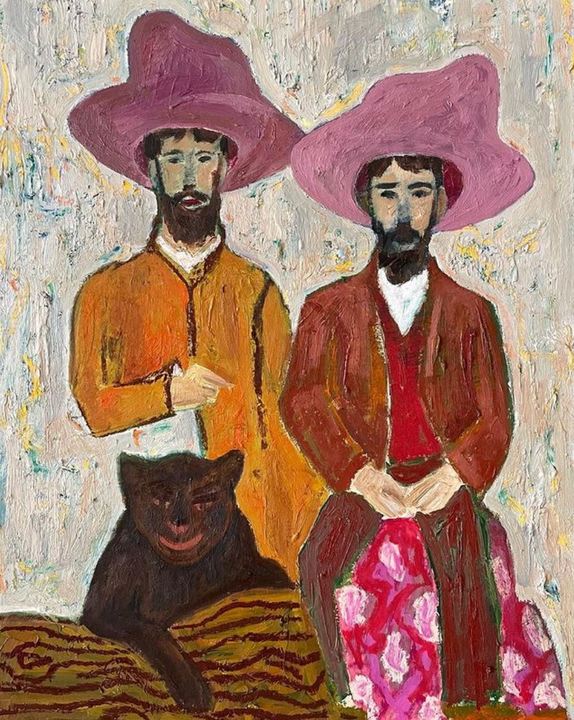

A few years ago, the algorithm on Instagram began showing me more and more artists. Ben Crase, a California-based artist, first popped up in my discovery channel. I would see his paintings over and over again: rancheros on horseback, sitting cross-legged in bars. In nearly every painting, the male figures wear absurdly large, bubble-gum pink hats.

%20%E2%80%A2%20Instagram%20photos%20and%20videos.jpg) Ben Crase (@gummy_beats)

Ben Crase (@gummy_beats)

Behavioural strategist Samuel McNerney has written about the relation between confirmation bias (our tendency to look for what confirms our beliefs while ignoring what contradicts them) and art. “Just as we only look for what confirms our scientific hypothesis or personal decisions, we likewise only listen to music or observe art that confirms our perceived notions of good and bad aesthetics,” he wrote in the Scientific American. Art that hangs in a museum or is displayed at a fancy art fair may be thought of as inherently good, simply because of the location - is the confirmation bias showing up in my algorithm?

My repeated ‘likes’ and bookmarks of Crase’s work led Instagram to prompt me towards Joshua Perkin, a British-born, Spain-based artist. Perkin is particularly interested in the concept of labour, and his figures, though not as thickly fleshed out as Crase’s, share a related sentimentality. They are posed in a similar way and their eyes emit the same defiant glow. Both artists use a muted tonal palette, with pops of colour, and both have a folk-y quality that feels like home. I fell in love with both artists’ work, rather naturally I thought, and smugly considered both of them good art – because I liked it. Or did I?

Does good art depend on context?

James E. Cutting, a psychology professor at Cornell University, has been studying the subjectivity of taste for decades. “Repeated exposure makes it easier to process an image, and the rapidity of processing makes one feel that you like it,” he tells Limna. “That is, we mistake speed for familiarity, and familiarity for liking-ness. This is particularly true when there is extended time between exposures.”

Repeated exposure makes it easier to process an image, and the rapidity of processing makes one feel that you like it. That is, we mistake speed for familiarity, and familiarity for liking-ness. This is particularly true when there is extended time between exposures.

The more you view a work of art, the more you may like it. “People default to cultural standards in any domain that they feel that they are not expert in,” notes Cutting. There are a few pieces of art that have made the rounds and been elevated in Western culture: Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘Mona Lisa’ (the most visited artwork in the world, though apparently people only stare at it for an average seventeen seconds), Pablo Picasso’s ‘Guernica’, Vincent Van Gogh’s ‘Starry Night’.

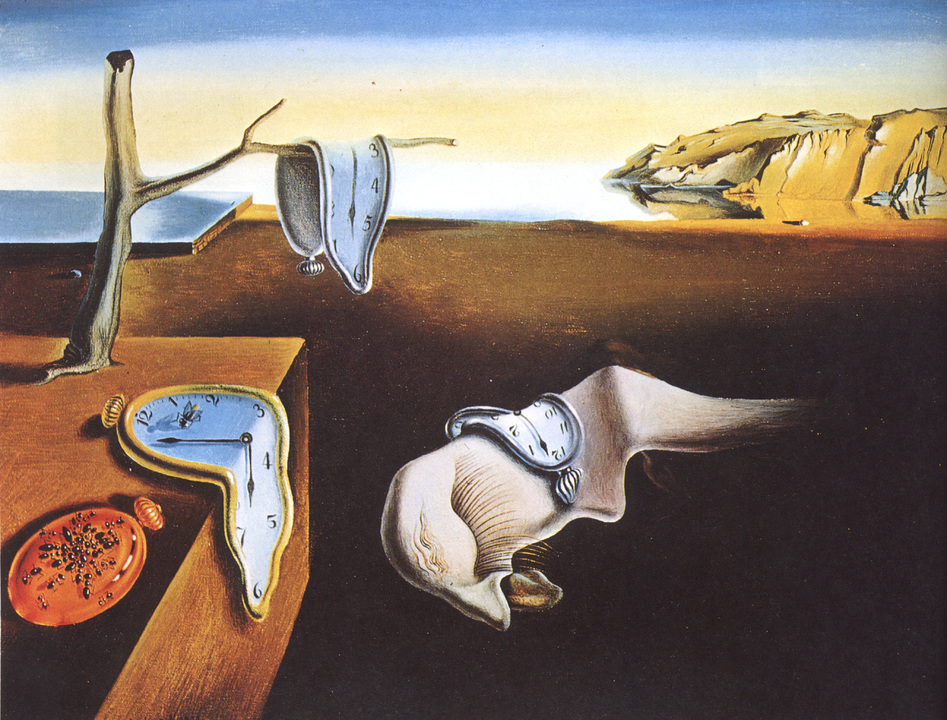

Salvador Dali, “The Persistence of Memory,” 1931

Salvador Dali, “The Persistence of Memory,” 1931

The images are repeatedly copied and given a new lease on life in secondary objects - silk scarves printed with Gustav Klimt’s ‘The Kiss’, notebooks embellished with Salvador Dali’s ‘The Persistence of Memory’. ‘Starry Night’, the painting that lives at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) is a masterpiece. ‘Starry Night,’ the fridge magnet, decidedly less so. In merchandising and commercialising a great work, it is rendered kitsch. Does the concept of “good” art change depending on the medium, then?

Instagram is flat, two-dimensional. I have never seen the curated artworks that pop up on my feed in person; they are relegated to little squares on my phone, and my exposure to artists like Crase and Perkin has been limited through the tiny, online world that’s been curated for me. And yet, I still have a visceral reaction to those works.

Neither artist warrant an exhibit at the MOBA - quite the opposite - yet in looking through their work, there are parallels with the Bostonian curation. In one of Crase’s paintings, ‘Old Crazy Legs’, two pink-hatted men pose next to…a dog? A small bear? A large cat? The creature has a flesh-coloured grimace that looks vaguely human-like. There’s an entire section of the Museum of Bad Art dedicated to our inability to accurately draw animals. But who is to say which artists belong there?

What’s class got to do with it?

While occasionally a highly self-aware artist will gift an artwork to the MoBA, the majority of the museum’s pieces are donated by people who find them in charity shops, yard sales and bargain bins. The correlation between what is “bad”, and its association with class and money, is difficult to ignore.

One of the pioneers in studying taste was the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu. In his 1979 study Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, he surveyed thousands of French citizens on their cultural preferences. He noticed a class stratification on taste: people tend to like what is associated with their economic milieu. As you ascend the class ladder, people’s reasons for choosing one particular piece of cultural work becomes increasingly abstract. Taste, in other words, is cultural hegemony.

Bourdieu rejected the notion that taste is something purely subjective or individualistic; no judgement is entirely pure. Furthermore, he posits that taste is something determined by members of society with a high volume of cultural capital. Our access to culture has become more democratic in the ensuing years, but, as Turner-prize winning artist Grayson Turner wrote decades later in an op-ed for The Telegraph, “Your taste depends on your class”.

There’s a painting in the MOBA’s “Zoo” exhibit entitled ‘Blue Tango’. Two blue dogs, one poodle, the other possibly a schnauzer, hold each other cheek-to-cheek as they waltz across a rust-coloured dance floor. (The piece, as are many in the MOBA’s collection, was purchased at a thrift store and donated to the museum). I love it just as much as I love the bizarre little creature in Crase’s Old Crazy Legs. The difference is that there’s only one I’d be willing to hang up in my house and stare at for years.

Ben Crase, Old Crazy Legs. 11 x 14 in. Oil, Oil Stick, Oil Pastel on paper.

Ben Crase, Old Crazy Legs. 11 x 14 in. Oil, Oil Stick, Oil Pastel on paper.

-min.jpeg)