Why Art Criticism?: The “crisis” seen in a different light

Much-disparaged yet absolutely essential, art criticism has been in a state of crisis for decades, in some circles. “Annoyed and fed up” with this discourse, the editors of Why Art Criticism? present a vast and potent history of the genre.

One of the most thrilling art books of the year has a simple, three-word title: Why Art Criticism? I know, I know, that question may not entice everyone. Hear me out. Weighing in at almost 500 pages, the volume compiles excerpts from more than 40 writers spanning about 250 years, and it amounts to a smorgasbord of art criticism in the most expansive sense of the term.

Its editors, Beate Söntgen and Julia Voss, asked an august group of art professionals to share examples of what they consider to be choice criticism. “We were very surprised by some texts because we wouldn’t have taken them for art criticism at first glance,” Söntgen told me. The selections highlight remarkable but little-known slices of art history and present a vast universe of ways of writing about art, in tones that are playful, mordant, confessional and brutally incisive. There is something here for everyone.

Ordered chronologically, the book begins with art-critic godhead Denis Diderot at the 1763 Salon in Paris, swooning over “a delicious painting” by Baptiste Greuze.

By 1905, Berta Zuckerkandl is leaking correspondence to support Gustav Klimt in a battle with the Education Ministry. There are exhibition reviews but also wild and inspiring essays, like Takashi Kashima’s 2013 charting of the peculiar phenomenon of artist Christain Riese Lassen, whose deliriously kitsch, dolphin-filled seascapes enticed frenzied buying in 1990s Japan.

To learn more about the compendium, I spoke with Söntgen, a professor of art history, and Voss, an art critic. They addressed the tired discussion about the death of art criticism and where this frequently maligned, absolutely essential genre of writing may be headed.

Jean-Baptiste Greuze, La Dame de charité, vers 1775. Image © Lyon MBA - Photo Alain Basset

Jean-Baptiste Greuze, La Dame de charité, vers 1775. Image © Lyon MBA - Photo Alain Basset

ANDREW RUSSETH: Why did you feel that now was the right time for a big reader of art criticism?

JULIA VOSS: It’s twofold. Beate and I have been art critics for a long time, and we often do workshops and teach about how to write art critique. We realized that there are many books on art criticism, its history, its role, its importance… but if you want to present a range of different ways to write art criticism, you basically have to find everything yourself. In a way, we thought about it as a teaching tool, to have a reader that assembles a very broad range of ways of writing art criticism.

The other thing is, we got annoyed and fed up with this very theoretical discourse. If you say art criticism is in a crisis, what are you talking about? And what country are you talking about? There is no such thing as art criticism in the singular. We wanted to make this discussion a bit more complicated and say: It’s a very broad, or very varied, technique of dealing with art. In order to inspire others, we show you different ways it can be done and how it has been done in different countries.

RUSSETH: I’m glad that you mention this often-discussed, looming sense of crisis. You write of the widespread conception that, due to economic pressures and even conflicts of interest, criticism has become “less polemic, less up for the fight,” but that the “texts in our reader shed a different light on the situation.” Why do you think people have been talking about art criticism in crisis for so long now?

BEATE SÖNTGEN: That’s a good question. I think the crisis has been there since the beginning. It’s always the question: Why do we need art criticism? If the Western idea of art is that it’s a very special thing, it’s critical in itself, it gives us a special view on the world, then why do we need art criticism to be talking about it?

Also this is maybe a Protestant thing, but some say: Well, art is a luxury and then art criticism is on top of that. There are more important things to talk about! Then there is this idea of the modern subject that constitutes itself in regarding art—feels itself seeing, imagining and reflecting and so on. This idea of the modern subject has been criticized, with good reason. Art criticism, which was so specific in forming this modern subject, has been thrown out with the modern subject.

VOSS: I think it’s also because art criticism is hard to grasp. It’s the little sister or maybe it’s even the oldest sister of art history. Art historians also have to judge, but they’re less upfront about it. Criticism is about judging. And I think mostly, it’s art historians, rather than critics, saying that art criticism is in crisis. I worked as the art editor of Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung for 10 years and I never felt that we didn’t matter—to the contrary. We had a lot of impact. You had to be very cautious choosing your words because you had such a large audience.

If you say art criticism is in a crisis, what are you talking about? And what country are you talking about? There is no such thing as art criticism in the singular — Julia Voss

RUSSETH: You mentioned judging as one thing that defines criticism. I am curious about how you delimited the scope of your book. What were the rules you set yourself and your contributors for what would count as criticism?

SÖNTGEN: We had to leave it open to our contributors because we wanted them to spell out their own criteria. This was the only rule. We didn’t say they needed to stick to this or that, as we wanted a large variety of what people practice and believe. Our aim wasn’t to reduce but to get more criteria, more genres and more styles. We even included catalogue texts, for example. You always praise, or be at least positive, when you’re writing a catalogue but such texts are a very important part of critique too, in reflecting your own stance and the way that you are addressing an art piece. We were very surprised by some texts when they came in because we wouldn’t have taken them for art criticism at first glance.

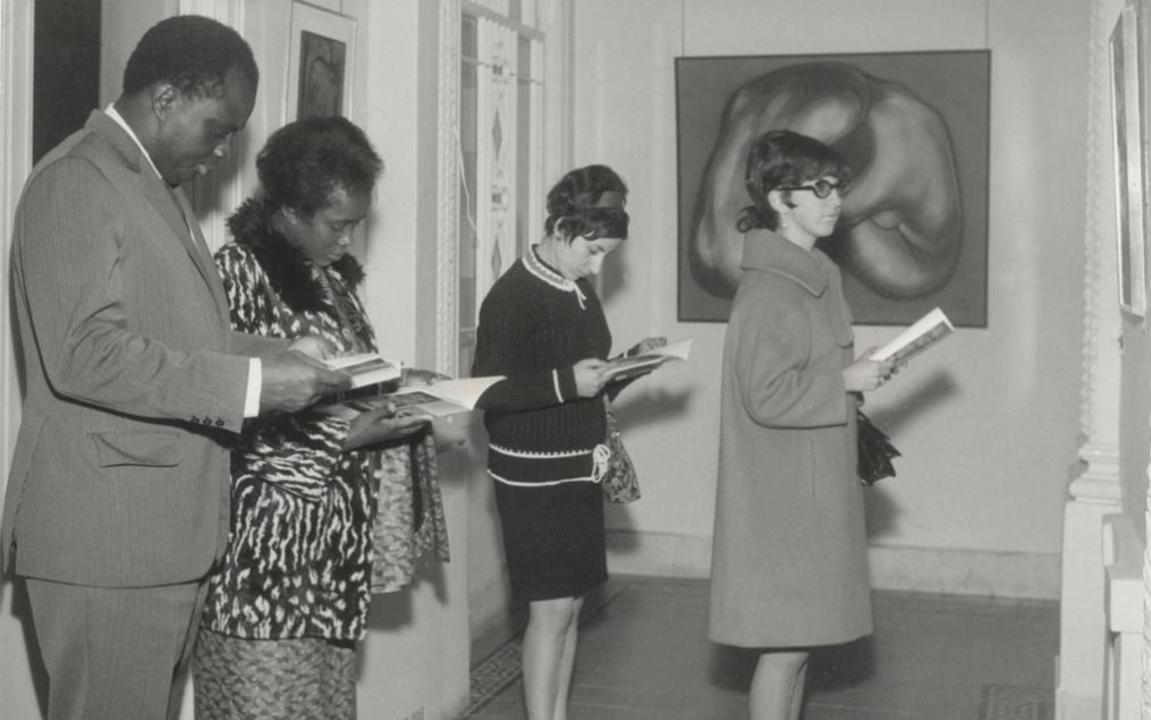

What was so important for us were the commentaries. Everybody discussed why they chose this text or position. Take, for example, the piece from Lebanon, by Victor Hakim [from 1968], that Monique Bellan picked. It’s just a report for a society magazine about what is going on in Lebanon, a country that was finding itself in terms of claiming culture of its own and resisting the West—or not—and all these important discussions. I would never have put this as a critique, but it’s an interesting thing to realise that it fits.

Visitors at the Sursock Museum’s 7th Salon d’Automne, 1967–1968, © Sursock Museum

Visitors at the Sursock Museum’s 7th Salon d’Automne, 1967–1968, © Sursock Museum

RUSSETH: Your book maps how art criticism has changed in reaction to political developments and shows how wars and revolutions have reshaped the field. For instance, the Soviet critic Sergei Tretyakov used war terminology in his writings from the 1920s. How are contemporary events, like Coronavirus and racial-justice protests, altering art criticism today? To put it another way, where are the important discussions?

SÖNTGEN: I think the most important thing that has come up with the discussions on Black studies and the Global South is how to write new narratives and how can we can appreciate things where there are no sources, or where there are just small traces left. I wonder what this could mean for art criticism, too.

VOSS: We are getting increasingly aware that, due to climate change, we also have to think about our idea of the museum. Perhaps having less centralized institutions is a better way to cope rather than having mega museums. It makes art criticism that doesn’t necessarily come from the centre stronger. I find this interesting.

RUSSETH: In the United States we have seen newspapers letting go of critics and culture writers in general. What is the situation like in Germany?

VOSS: We are kind of in a privileged situation because globally, German newspapers still have the most pages on culture every day. Still, the digital change is happening—it’s a bit slower, maybe because Germans on average are a bit older than people in other countries. From a long-term perspective, the same things are happening everywhere. Positions at newspapers are less well-paid than before and there are fewer people working there.

Yet the interesting thing is that we have seen the rise of a very critical—even activist—art criticism movement that is stronger than ever. We have seen artists and art critics coming together and doing things like Nan Goldin’s anti-Sackler movement or other protests against certain museum trustees. It is a completely new situation. Although social media killed some critical oppositions, I think it also gave rise to a whole new movement that wasn’t there before.

Nan Goldin ©Antonio Zazueta Olmos.

Nan Goldin ©Antonio Zazueta Olmos.

RUSSETH: You’re both teaching at university level and you mentioned earlier that you see the book as a teaching tool. How do you go about helping students learn to write criticism?

SÖNTGEN: We encourage them to practice themselves—to reflect their own criteria and their ways of writing. It’s a different thing if you are writing about art criticism or if you are doing it. When you’re doing it, you say, OK, what are my criteria? I think this is the most important thing to bring students. Why am I judging, or even only describing, in this way, and why do I respond to an art piece and why not?

RUSSETH: The book will help them to figure out their approach. It presents incredible options.

VOSS: I stopped being a newspaper editor in 2017, and I recently thought, I would have loved to have a book like this. On some grey day, to open it and say: Inspire me. Help me. Because, really, there are so many different ways, styles and formats in there, and I think this can be a big inspiration.

The conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

-min.jpeg)