Why do contemporary artists love reviving historic genres?

If contemporary art holds a mirror to the present, it is also a portal to the past. Limna explores why artists today so often look towards the past.

In a world that is so preoccupied with the future, it’s curious that contemporary art so often turns towards the past. For example, this year’s Venice Biennale – a fair dedicated to the latest innovations in contemporary art – takes as its starting point The Milk of Dreams, a text by Leonora Carrington, a Surrealist figure who rose to prominence nearly a century ago. But we also see a return to history in the works of numerous contemporary artists, many of whom are dominating the secondary market, gallery and museum exhibitions.

One might argue that much of contemporary art is stuck in history - have we run out of original ideas? On the other hand, the desire to revisit the past reveals that there is something inherently retrospective about our culture. We glorify and continue to learn from what came before, explaining why historic genres constantly reappear in the present. But as once allegedly articulated by Picasso, “good artists borrow, great artists steal”, all influential artists have – to an extent – appropriated from their predecessors.

In the words of the influential cultural theorist Terry Smith, ‘many artists today use art historical reflection to tackle pressing issues about what it is to live in the present

According to Donald Kuspit, contemporary culture can be defined as “the insecurity of being ephemeral”. By this he meant that one characteristic of the contemporary is to be fundamentally “incoherent” – artists create some permanence by returning to history, whether in the form of the Renaissance, Dutch still life, Rococo, Abstract Expressionism or Surrealism (the list goes on). In the words of the influential cultural theorist Terry Smith, “many artists today use art historical reflection to tackle pressing issues about what it is to live in the present.”

From top to bottom: Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, 1995/2009; Colored Vases, 2007-2010.

Installation view of Ai Weiwei: According to What? at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington D.C., 2012

From top to bottom: Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, 1995/2009; Colored Vases, 2007-2010.

Installation view of Ai Weiwei: According to What? at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington D.C., 2012

Let’s take the work of the Chinese artist Ai Weiwei, whose replicas of Han Dynasty vases are overlaid with the familiar logo of Coca-Cola. Ai’s work speaks to the globalised and capitalistic nature of contemporary culture, whilst simultaneously referencing the histories of his native China, and also American Postmodernism – Andy Warhol’s appropriation of Coca Cola branding immediately springs to mind. In 1995 Ai had pushed this iconoclastic gesture to the limits in Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn. The symbolic act of destroying a historical artefact ironically created a highly valued work of contemporary art, speaking to the kind of ephemeral nature of the ‘contemporary’.

The artist-brothers Jake and Dinos Chapman are known for being equally provocative and often appropriate past styles, in particular images of horror and gore typically found in works by the early Netherlandish painter Hieronymus Bosch, or the works of the Spanish artist Francisco de Goya. Disasters of War (1993) directly references the eponymous etchings by Goya made during the Napoleonic invasions of Spain in 1808, when the Spanish artist intended to rally indignation and protest against the conflict. The Chapman’s diorama-like sculptural work reveals plastic figurines with severed and bloody limbs, evoking the Spanish artist’s expressionist drawings, but instead utilising such images to capture modern society’s absurd desensitisation to scenes of brutality and violence.

Jake and Dinos Chapman, Insult to Injury (detail), 2003. 80 hand water coloured reworked Goya etchings, 37 x 47 cm (each). © Jake and Dinos Chapman. Courtesy of John McEnroe Gallery.

Jake and Dinos Chapman, Insult to Injury (detail), 2003. 80 hand water coloured reworked Goya etchings, 37 x 47 cm (each). © Jake and Dinos Chapman. Courtesy of John McEnroe Gallery.

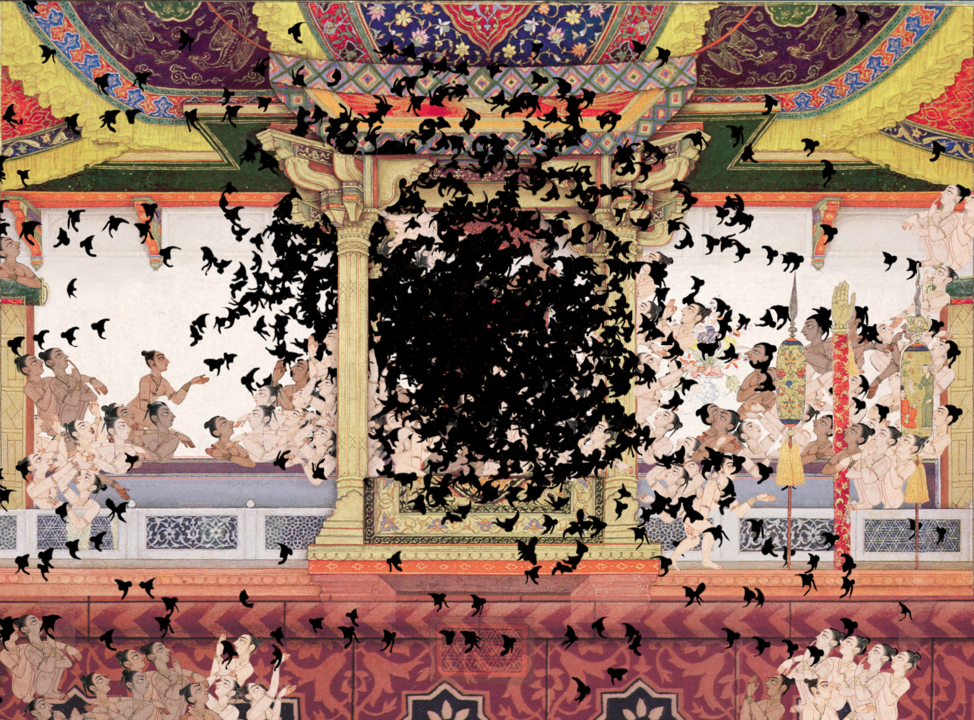

Other creatives referencing their country’s cultural and historical heritage include contemporary Pakistani artists such as Shahzia Sikander and Imran Qureshi, both of whom studied at the National College of Arts in Lahore, Pakistan – a school credited for the metamorphosis of the historic Indo-Persian and Mughal miniature into the modern art form. The genre of miniature painting, which reached its pinnacle in the royal courts of the Mughal Empire between the 16th and 18th centuries, is revived and subverted by both artists, to offer explicit or subtle commentaries about postcolonial, contemporary life. Today both Qureshi and Sikander rate highly on Limna’s ‘Cultural Recognition’ rating (with Sikander at 77, and Qureshi at 72) and continue to be collected by museums.

Shahzia Sikander, still from SpiNN, 2003. Digital animation with sound, 6 min, 38 sec Jeanne and Michael Klein; Promised gift to the Blanton Museum of Art, University of Texas at Austin © Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: Sean Kelly, New York

Shahzia Sikander, still from SpiNN, 2003. Digital animation with sound, 6 min, 38 sec Jeanne and Michael Klein; Promised gift to the Blanton Museum of Art, University of Texas at Austin © Shahzia Sikander. Courtesy: Sean Kelly, New York

In Sikander’s works such as SpiNN (2003), a painting created for a digital animation, the artist plays upon the traditions of the miniature to challenge stereotypes about Muslim women. Whereas traditional Indian manuscript paintings typically featured only a single prominent gopi (a female guardian) such as Radhaz (the favoured consort of Krishna), in Sikander’s contemporary rendering, the number of gopis multiplies and dominates the picture plane, giving all the female figures the agency of Radha and thus speaking to the power of a collective feminine space.

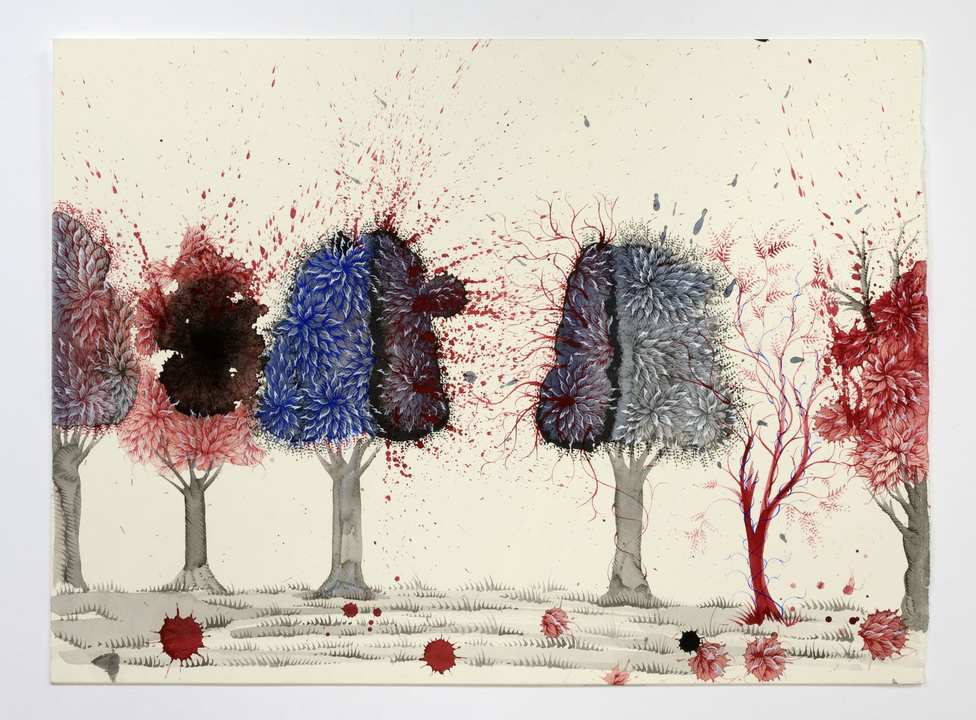

Like Sikander, Qureshi challenges gendered stereotypes through his modern miniatures, in particular, the types of Islamophobic tropes perpetuated by Western media, for example, that Muslim men are associated with extremism and violence. Qureshi embraces the poetry and delicacy of the historic genre to offer an alternative and more compassionate image of the modern Muslim man, countering many dehumanising stereotypes found ubiquitously in the West. While he plays on imagery of violence, upon closer inspection, spatters of red blood – seen in the artist’s site-specific installations – take on the form of ornate decoration. What at first appears frightening is in fact evocative of natural forms or delicate calligraphy, harking back to the refined aesthetic motifs of the Mughal miniature. Just as Mughal court painters once captured key moments of history to preserve the legacy of royal rulers, Qureshi repurposes the genre to confront history and debunk harmful narratives.

Imran Qureshi, Story of Two, 2019. Gouache on paper © Imran Qureshi. Photo: Charles Duprat Courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac gallery, London · Paris · Salzburg · Seoul

Imran Qureshi, Story of Two, 2019. Gouache on paper © Imran Qureshi. Photo: Charles Duprat Courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac gallery, London · Paris · Salzburg · Seoul

One of the most commercially successful emerging artists to innovatively revise historic traditions is Flora Yukhnovich, who, as the Limna app supports with +27% Momentum, has exploded onto the contemporary art scene over the past few years. The London-based painter creates large-scale abstractions that revive the whimsical genres of French Rococo and Venetian Renaissance painting. By adopting a palette of soft pinks and pastel blues in flurries of swirling paint, she evokes the celestial visual language of painters such as Tiepolo and Titian, or French academy artists such as François Boucher and Antoine Watteau. In the words of curator Eleanor Nairne, the artist’s sensual paintings “hark back to scenes of frolic and seduction in Rococo painting” but also evoke the style of painting that emerged in post-war American abstraction – the all-over gestural canvases of Jackson Pollock, or the softer hues of paint adopted by Helen Frankenthaler. An artist who engages with internet and Instagram culture, her painterly vocabulary – reminiscent of the frivolous hedonism of Watteau’s fêtes gâlantes paintings in pre-Revolutionary France – also resonate with the superficial and fleeting culture of the Millennial online world.

Flora Yukhnovich, I’ll Have What She’s Having, 2020.

Flora Yukhnovich, I’ll Have What She’s Having, 2020.

If contemporary art holds a mirror to the present, it is also a portal to the past. As Arthur C. Danto proclaimed, contemporary art exists at the ‘end’ of history: it must constantly reiterate past styles and periods of art history. Whether we believe the idea that art has a finite trajectory or not, it is inextricably connected to its historical roots. By looking towards the past, we can cherish what came before, while making sense of our place in the present.

-min.jpeg)